Writing White Privilege, Race, and Citizenship: Reading Angela Davis, Toni Morrison, Claudia Rankine and Walt Whitman

Ileana Jiménez

Intended Audience: High School Students

Overview: This lesson pairs texts in conversation to engage students in examining white privilege and supremacy, race and racism, and citizenship.

Scope and Sequence: The lesson begins with a shared writing exercise about, and discussion of, Toni Morrison’s short essay, “Mourning for Whiteness,” which was published in the November 21, 2016 issue of The New Yorker following the election. This text provides the foundation for exploring the ways in which both the recent election cycle, and the selection of the incoming administration, provide a critical and urgent opportunity to analyze white privilege and supremacy, race and racism, and citizenship.

Following both a close and creative reading of Morrison, students will then read and write about an excerpt from Angela Davis’s 2009 speech, “Democracy, Social Change, and Civil Engagement;” an excerpt from Claudia Rankine’s Citizen; and selections from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.” Through a series of freewrites, students will create an archive of pieces that they can then use as the material for writing a poem, prose poem, or other creative piece of writing that reflects their personal and political experience of white privilege and supremacy, race and racism, and citizenship.

Common Core Standards for Literacy

Objectives

The lesson objectives are to:

- Process and reflect on the recent election from both personal and political perspectives, using literature by mainly women of color and one white male author to help students understand their pre- and post- election consciousness around race, privilege, and citizenship

- Annotate and close read pieces of literature by a range of classic and contemporary authors who explore themes of white privilege and supremacy, race and racism, and citizenship in their work and how these themes cross cultural, racial, and historical contexts

- Explore personal experiences of white privilege and supremacy; race, racial identity, racism and citizenship within structures such as school, media, politics, family and friendships

- Explore notions of citizenship that go beyond technical definitions

- Write a range of pieces, from freewriting to poems and prose poems and beyond, to capture student thinking on the election in relation to their own identity, culture, and politics

Essential Questions

- Given the recent election, how do we begin to reflect on and process through our emotions and opinions about critical themes such as white privilege and supremacy; race, racial identity, and racism; and varying notions of the idea of citizenship?

- We started the year talking about citizenship and how authors explore this idea in literature. What are our thoughts on this theme post-election as opposed to what we thought pre-election? In what ways have we remained the same, shifted, and/or deepened our ideas and definitions?

- How might Toni Morrison, Angela Davis, Claudia Rankine, and Walt Whitman provide us the language we need to understand power, privilege, and oppression in a post-election world?

DAY ONE: Toni Morrison’s “Mourning for Whiteness”

Throughout the class session (45-60 minutes), students will engage in a series of focused freewrites on Morrison’s “Mourning for Whiteness,” New Yorker, November 21, 2016.[1] The following exercise is adapted from writing practices created by the Bard Writing and Thinking Institute at Bard College.

- Read the piece silently.

- Read the piece aloud popcorn style (without raising hands, one student at a time).

- Underline at least three moments that spoke to you or that resonate with you in some way; it can be a word, a line, a phrase, a sentence; number these moments 1, 2, and 3.

- Engage in a choral-style reading of the piece: ask one student to read the opening paragraph of the essay and her selection #1; followed by other students reading their #1; followed by the first student’s #2, and other students’ #2; and so on until everyone has read all three of their selected moments.

- The first student should then close the choral reading by reading aloud the final paragraph of the essay.

- Select one of the moments that you numbered or select a new line and write about that phrase, line, or sentence with these prompts in mind:

- What does this line mean to you?

- What might this line mean to Morrison?

- How does this line help us to reflect on the election?

- The teacher should then read aloud the essay again stopping at the end of each paragraph to hear student writing on the lines they selected. All students should read what they wrote. This is a read-aloud of the freewrites and not a discussion, so there should not be any cross-talk or dialogue at this time.

- At the close of the reading, students should then reflect on the following prompts:

- What do you understand now about this reading that you did not before?

- What did you hear your peers say that deepened your understanding of the reading or that surprised you, or that you agreed or disagreed with? Explain.

- How did this exercise help us to begin reflecting on white privilege and supremacy, race and racism, and citizenship in relation to the election?

- Large group discussion of the reading and writing.

Homework: Read selections from Claudia Rankine’s Citizen.[2] Teachers can select any set of pages that reflects the kind of work on white privilege and supremacy; race and racism; and citizenship that they want to do with their students.

DAY TWO: Angela Davis and Claudia Rankine on Race and Citizenship

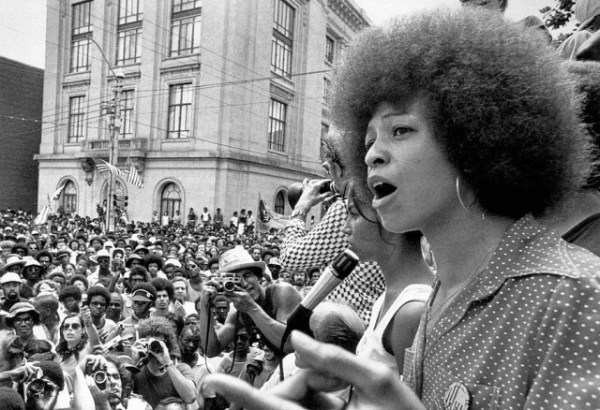

Students will begin class by reading the following excerpt from Angela Davis’s “Democracy, Social Change, and Civil Engagement,” from her book, The Meaning of Freedom: And Other Difficult Dialogues. This essay was originally delivered as a talk at Bryn Mawr College in February 2009 (The Meaning of Freedom: And Other Difficult Dialogues).[3]

As we all know, the term “civil rights” refers to the rights of citizens, of all citizens, but because the very nature of citizenship in the United States has always been troubled by the refusal to grant citizenship to subordinate groups—indigenous people, African slaves, women of all racial and economic backgrounds—we tend to think of some people as model citizens, as archetypal citizens, those whose civil rights are never placed in question, the quintessential citizens, and others as having to wage struggles for the right to be regarded as citizens. And some—undocumented immigrants or “suspected” undocumented immigrants, along with ex-felons or “suspected” ex-felons—are beyond the reach of citizenship altogether. –Angela Davis, “Democracy, Social Change, and Civil Engagement,” Feb. 2, 2009.

- Ask a student to read aloud the passage.

- Select a phrase or sentence from this passage and write from this prompt:

- What does this line or phrase mean to you now post-election?

- How is “your” line or phrase or passage, as a whole, in conversation with yesterday’s reading of Morrison’s essay?

- How does the passage, as a whole, complicate, expand, or deepen your understanding of citizenship?

- Students should share and read aloud from these freewrites; this can be done as a whole group, pair-shares, or a combination.

- Then ask students to keep in mind these reflections as they transition to Rankine’s Citizen.

- Read aloud the selection.

- Select a phrase, sentence, or passage from the excerpt and write:

- Although we have not read the entire book, given the selected excerpt, why would Rankine have titled her work, Citizen? Write about a line or phrase in the excerpt that allows you to explore why.

- Sharing of freewrites.

- Large group discussion. How are these texts in conversation with each other?

Homework: Selections from Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” sections 1, 2, 6, 16, 24 are suggested, but teachers can select any combination that suits the work they want to engage with students on notions of selfhood, democracy, diversity, and citizenship.[4]

DAY THREE: Walt Whitman on Democracy, Diversity, and Citizenship

Students will have read sections 1, 2, 6, 16, 24 of “Song of Myself” for homework. Engage students in re-reading these sections aloud in class and with each section, conduct a close reading discussion, stopping to discuss the speaker’s voice, tone, imagery, and language. It will be important to discuss the dramatic situation of each section to highlight what the speaker explores in relation to selfhood, democracy, diversity, and citizenship.

After reading and discussing these sections, students should also connect Whitman’s poetry to the readings by Morrison, Davis, and Rankine.

- How are each of these writers complicating and deepening our notions of citizenship? Of democracy? Of power and privilege? Of systems of oppression? Of liberation and freedom?

DAYS 4-7: Song of Self Poetry Writing Project

For this project, students will create an original poem inspired by their collective reading and discussion of Toni Morrison, Angela Davis, Claudia Rankine, and Walt Whitman. Given their anchoring of these discussions, in relation to white privilege and supremacy; race and racism; and citizenship, both pre- and post- election, students should use their freewrites and reflections on each of these writers as a springboard for examining their own notions of what it means to be a citizen and to shape these ideas into a poem.

For example, in his poem “Song of Myself,” Whitman writes about what he loves and what he hates, about his beliefs and his assumptions, about his personal experiences and the collective experiences of the nation. Most importantly, he seeks to explain and expose his true self to the reader: “Through me forbidden voices…voices veiled, and I remove the veil.” Students should be asked: What do you want to explore or “remove the veil” about yourself and your identity and your lived experience in both the pre- and post- election world? What do you hope to unveil as your truth as a “citizen” in your city and/or country? How can you do so through writing?

Teachers should use days 4-7 to help guide students in the shaping of their poem or other creative piece, either with further prompts and freewriting, or additional readings. These days should be used as individual conference days as well as time for in-class writing and shaping of their poems, prose poems, or other pieces. At the end, students will assemble and revise their writing into one cohesive piece and present their “Song of Self” to the class.

Works Cited

Davis, Angela. The Meaning of Freedom: And Other Difficult Dialogues. San Francisco: City Lights, 2012.

_______. ““Democracy, Social Change, and Civil Engagement” — Angela Davis at Bryn Mawr College, February 2, 2009.” Black Independent Film – Spring 2014, Bryn Mawr. Bryn Mawr College, 30 Apr. 2014. Web. 07 Dec. 2016.

Morrison, Toni. “Mourning for Whiteness”or “Making America White Again.” The New Yorker. The New Yorker, 16, Nov. 2016. Web 07 Dec 2016.

Rankine, Claudia. Citizen. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2015.

Whitman, Walt. “Song of Myself.” Leaves of Grass: Authoritative Texts, Prefaces, Whitman on His Art, Criticism (Norton Critical Edition). New York: W.W. Norton, 1985.

Notes

[1] Toni Morrison, “Mourning for Whiteness” or “Making America White Again,” November 21, 2016,

[2] Claudia Rankine, Citizen, (Graywolf, 2015).

[3] Angela Davis, The Meaning of Freedom: And Other Difficult Dialogues (City Lights, 2012) and video,

[4] Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself,” Leaves of Grass (1892)

Hope, Action, & Freedom in Times of Uncertainty

Conra D. Gist, Ph.D., Angela Davis Johnson, & Tyson E.J. Marsh, Ph.D.

Intended Audience: Middle and High School students

Overview: This lesson plan is the outgrowth of a Spring 2016 Black History Bulletin (BHB) Issue on Black Youth Activism, Guest Edited by Dr. Conra D. Gist. The purpose of the issue was to a) explore Black youth activism as situated historically in different disciplinary spaces with diverse epistemological perspectives, cultural traditions, and social-economic-political-historical legacies; b) grapple with youth empowerment from the viewpoints of a critical educator, artist, and preacher who build emancipatory and intellectual bridges between historical struggles and contemporary challenges and possibilities; and c) cultivate intellectual spaces that invite and encourage the generation of transformational and emancipatory ideas. Critical Educator, Dr. Tyson E.J. Marsh, grappled with the question, what is critical educational activism and how does it equip students to consume and generate emancipatory knowledge that elevates their political and social consciousness? Activist Artist, Angela Davis Johnson, made sense of the question: How can art function as a creative tool for personal and community freedom and justice work? Collectively our work is a synthesis and representation, or reversioning, of the work of an artist, teacher educator, and leadership educator working collaboratively to produce counter-narrative knowledges and educational possibilities for youth.

At a time when uncertainty and fear threaten to silence the spirits of hope, action, and freedom that embody our democratic project in the United States through imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (hooks, 2004), it is vital that we assert pedagogies, practices and purpose that continue to advance the justice work of freedom. This lesson plan takes aim at such work by focusing on the ways we can work as educators and organizers to clear the space and deconstruct both the messiness of divisive and dangerous rhetoric, and the sociopolitical realities of injustice, by utilizing cultural scripts, images, and/or artifacts as a window to look through the emotional realities evoked in hostile and alarming environments. The ability to think in critical and transdisciplinary ways that honor the experiences and voices of youth, while also challenging them to act in ways that challenge the status quo, is the cultural work we encourage educators and school leaders to take up through the teaching of this lesson.

Scope and Sequence: Given our commitment to cultivating educational and learning spaces that are healing and transformative environments for youth, this lesson plan attempts to center the voices and experiences of middle and high school youth through three major components: 1) clearing a space for youth to ground themselves in their truth by asserting intentionality and purpose; 2) looking to discover stories within themselves and recognizing the power of their own voice by examining contemporary examples of artists modeling this work; and 3) walking through a cultural reversioning activity and unpacking and synthesizing experiences with the process while imagining new opportunities for action and activism.

In light of the tireless assault waged on communities of color through an intersection of unjust practices and systems of oppression, and in particular the acute attack on communities of color through state-sanctioned police violence, instructional tools and imagery employed with youth must provide opportunities to grapple with and make meaning of unjust realities they must often confront in their day to day lives. To achieve this goal, the lesson plan opens with a set of “clearing space” practices that create a context for youth to bring their authentic selves to the classroom community. These practices are informed by the Activist Artist work of Angela Davis Johnson who engages in this work with various community activist groups across the United States.

Once the purpose and intention has been set to open the space, the second component of the lesson challenges the class to grapple with the idea of stories (e.g., oral storytelling, testimonies, narratives) being utilized as a type of practice and vehicle of affirmation, critique, community building and resistance when making sense of the world around them. This portion of the lesson challenges students to discover stories within themselves and recognize the power of their own voice by examining contemporary examples of artists modeling this work.

The album “A Seat at the Table” by Solange is utilized as a medium to reflect the idea of discovering stories by considering the broader narrative the artist communicates through the title of her album, the particular audio recorded testimonial stories from her mother, father, and multi-platinum artist Master P, and the multiple mini-narratives interwoven within and across verses of particular songs. Read more on Solange’s process.

The third component of the lesson builds a bridge between the idea of storytelling as a critical practice in general, to consider cultural reversioning as a type of instructional tool that can be utilized to rewrite and reimagine social scripts of despair and injustice in ways that honor and reflect the experiences of youth. To do this, students apply the idea of cultural reversioning in practice in a two part process: 1) listening to “Mad”- a song by Solange and Lil Wayne – and rewriting the lyrics based on a set of questions that foster critical thought in small groups; and 2) synthesizing ideas discussed in the group to clips of paper to reimagine images of Black youth; in this case, students create a collage image of Mike Brown in his cap and gown. The lesson then concludes with student discussion about the cultural reversioning process and asks students to consider implications for socially just praxis.

Common Core Standards

Key Ideas and Details

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

Craft and Structure

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

- Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

- Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

- Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse formats and media, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.*

- Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

Comprehension and Collaboration

- Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

- Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

- Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

Presentation of Knowledge and Ideas

- Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

- Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations.

National Core Arts Standards for Visual Arts

Anchor Standard 1: Generate and conceptualize artistic ideas and work

Anchor Standard 2: Organize and develop artistic ideas and work

Anchor Standard 6: Convey meaning through the presentation of artistic work

Anchor Standard 7: Perceive and analyze artistic work

Anchor Standard 8: Interpret intent and meaning in artistic work.

Anchor Standard 10: Synthesize and relate knowledge and personal experiences to make art

Anchor Standard 11: Relate artistic ideas and works with societal, cultural, and historical context

NOTE: The authors modeled this lesson at the 2016 Association for the Study of African Life and History (ASALH) Conference in Richmond, VA.

Objectives

Students will be able to:

- Create a space to reimagine their lives in the face of present-day uncertainties and produce an image that counters narratives of lack with possibility and achievement

- Discuss how everyday people find hope and liberatory possibilities through storytelling

- Reflect, describe, and address the ways in which their lives can be impacted by social and systemic inequality

- Engage in a cultural reversioning process as a freedom building practice

- Synthesize key ideas processed in class discussion and generate strategies for taking up justice work in their everyday lives

Essential Questions

- How do we create spaces to reimagine our lives in the face of uncertainty?

- How are our lives impacted and / or informed by social and systemic inequality (e.g., white supremacy, sexism, racism, homophobia)?

- Why do people seek hope and liberatory possibilities in the face of uncertainty and difficulty?

- How can stories be utilized as sites of healing and resistance?

- What is cultural reversioning and how does it function as the practice of freedom?

LESSON PLAN

Part 1: Clearing Space and Grounding Self

Clearing space is part of a contemplative art practice that integrates meditation, deep breathing exercises and visualizing to center oneself. This practice can serve as a healing tool to challenge the sting of poverty, state-sanctioned violence and displacement (For additional information). It helps to prepare one for the weight and impact of digging deep within yourself and confronting what you may find. Recognizing that there is power and creativity in creating healing spaces in community, it enables people to build deeper connections and remember and realize the common ties that bind humanity. In times of uncertainty it can be seen as the practice of freedom.

Step 1. Create a calming aromatic environment (for example allow students to smell or rub on essential oils like lavender, rosemary and/or burn sage if permitted on school grounds)

Step 2. Lead a meditative breathing exercise. Ask students to inhale positive thoughts (trust, confidence,love) and exhale negative feelings (mistrust, insecurity, hate). Repeat three times.

Step 3. Continue breathing exercise by asking students to imagine their favorite color, person, or place as they breathe deeply to center themselves in a peaceful state of mind.

Step 4. Set the intention by stating what the class hopes to gain out this activity.

Part 2: Discovering Stories Within

Explain to students they will now grapple with the idea of stories (i.e., oral storytelling, testimonies, narratives) being utilized by people as a type of practice and vehicle of affirmation, critique, community building and resistance when making sense of the world around them. For the purpose of this lesson, students are being challenged to discover stories within themselves and recognize the power of their own voice. In order to do this they will first examine a contemporary artist example unpacking the stories they have unfolded from her life, and then consider connections and implications to their personal stories.

Solange reflects her idea of discovering stories within ourselves in her album, “A Seat at the Table”, because she communicates a broader narrative through the title of her work. The audio recorded testimonial stories from her mother, father, and multi-platinum artist Master P, and the multiple mini-narratives interwoven within and across verses of particular songs (See interview explaining the album themes) emphasizes how the richness of layered meanings inform our lived realities. Guided by Solange, her process, reflective and powerful voice (See video referenced above, and have students read a synopsis of the album), students will explore their own voices and the experiences and lived realities that inform them.

After students have read the resources above, the instructor should pose the question:

What feelings, emotions, experiences inform Solange’s work?

After documenting samples of the feelings, emotions, and experience on the board, students should be divided into small groups and asked to discuss the following questions:

- What is a significant story and experience that has shaped your voice?

- How are your stories, experiences, and voice affected by white supremacy?[1]

- Have you experienced or witnessed racism, sexism, or homophobia?

- What are your fears or concerns surrounding thoughts of the future? What are your hopes?

- What is it like to live in your current neighborhood? What changes would you like to see happen in your local community, state, and country?

Part 3: Cultural Reversioning and Critical Discussion

After students engage in discussions about significant stories from their own lives explain that they will now engage in a cultural reversioning activity. Below is a brief conceptual description to anchor your understanding. You can use this background information to provide students a basic definition and framework of the practice they will take up. For further reading, additional information can be found in Keyes (2004) Rap Music and Street Consciousness.

Cultural Reversioning: Drawing from and building on the work of Gilroy (1993), Keyes (2004) developed the concept of cultural reversioning to describe the way in which African peoples brought their cultural understandings and ways of being in the world to bear on their experiences in the new world. Describing the concept of cultural reversioning as “the foregrounding (consciously and unconsciously) of African-centered concepts”, Keyes (2004) contends that:

In the New World, Africans were enslaved and forced to learn a culture and language different from their own. In the face of this alien context, blacks transformed the new culture and language of the Western world through an African prism. The way in which they modified, reshaped, and transformed African systems of thought resonates in contemporary culture. (p. 21)

Contributing to the development of a hybrid culture, the first African Americans drew upon and reversioned their indigenous African practices to serve as tools of survival that would assist them in navigating, surviving, and resisting oppression, from genocide and slavery to mass incarceration (Alexander, 2012). This hybridization coupled with oral traditions and communicative practices contributed to the reversioning of African-centered concepts that would help them name and discuss their experiences, while also utilizing them to interrogate their condition. Keyes (2004) attributes and identifies the development of distinct African American expressive traditions including, but not limited to, field hollers, the blues, jazz, sermons, and hip hop culture to the process of cultural reversioning, which ultimately served as key locations for resistance to white supremacist state-sanctioned violence. Operationalizing this concept, Keyes (2004) presents rap music and hip hop culture as the culmination of these cultural forms of expression and tools for survival.

However, just as Black cultural practices and traditions can be reversioned, revitalized, and reinvigorated, that we must continue to insist that #BlackLivesMatter in 2016 is indicative of the way in which white supremacy, state sanctioned violence, and technologies of racism have also evolved. Compounded by the election of Donald Trump to the most powerful office in the world, the potential appointment of white supremacists to the White House Staff, and the rise of violence aimed at communities of color, it is critical that we prepare Black youth to understand that their cultural practices and traditions are rooted in resistance. Once again, these tools must be reversioned.

The Cultural Reversioning Process

In order to operationalize the concept and pedagogical value of cultural reversioning, we then take students through the following activity.

- Introduce artist/author and contextualize the text: In this case, the artist will be Solange (see video references listed in part 2 of the lesson plan for additional information).

- Listen to song: Explain that the class will focus on the song “Mad” by Solange and Lil Wayne, which can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTqNemB6mio Print the lyrics and have students listen to and follow along with a song that captures contemporary articulations of the struggle against white supremacist state sanctioned violence.

NOTE: Depending on the nuances of your local context and struggle against white supremacist state sanctioned violence, we recommend choosing a song/resource that speaks closely to that struggle.

- Use heart lenses to reflect on lyrics: Once students finish listening to the song explain that there are different “heart lenses” that can be utilized for engaging with lyrics: thinking, feeling, and seeing. Share the questions framing each of the heart lenses with the students.

Thinking: How do we teach/challenge Black Youth in ways that cultivate a critical consciousness in a productive and transformational fashion? How do we as leaders—scholars—activists—artists challenge Black youth to take up this work?

Seeing/Hearing: What will we see and hear as evidence of Black youth walking in their power? How do we create spaces for Black Youth to voice their experiences and reimagine their lives as free and limitless beings?

Feeling: What feelings are most apparent in Black youth expressions about the state of Black life in America? What can we do to be sure we are providing spaces for Black youth to express grief, aspirations, fears, loves? What emotions do we experience as artists/scholars/activists working to create more humane dwelling spaces? How can emotions be expressed, channeled, and /or molded in ways that work on the side of justice for the betterment of self, family, and community?

Next, explain that students will be organized in groups of three with each group focusing on a particular heart lens (thinking, feeling and seeing/hearing). Each group should first grapple with the assigned overarching heart lens questions to consider their own experiences and make connections to lyrics where appropriate.

- Rewriting responses to lyrics: Distribute the heart lenses handout to students (see attached). Explain that each heart lens focuses on selected verses from the song “Mad.” As a group (or in partnership depending on classroom dynamics) have students begin engaging in the cultural reversioning process by writing the verses through the lenses of their own experiences and tapping the stories within in ways that honor their own experiences.

- Auditory to Visual: Each group will receive color coordinated pieces of construction paper that will be used to make an image. In this case the image will be a cutout of Mike Brown, but you can select any image that is reflective the local struggles and experiences of your student population. Prep work is needed to create pieces that, when joined together collectively portray the image of Mike Brown.

First, examine the image and with a pencil create a silhouette of the subject on a large posterboard. Next, reduce the design in simple lines; no color (simple line drawing resource). Once the simple line drawing is established, fill the image in with pieces of construction paper that are shaped to the contours of the image, color coded to reflect resemblance, and numbered so students will know where to place each slab of construction paper.

For this lesson plan the slabs of construction should be divided in three groups (1-3); each representing one of the heart lenses (e.g., thinking (1), feeling (2), seeing/hearing (3). Each group member will receive a slab of construction paper to then translate their reversioned lyrics in a way that reflects their individual artistry; their handwriting is their own unique expression that will be eventually represented visually within the broader collective image.

- Visual to Kinesthetic: Students will then take their individual artistic pieces of construction paper and place on the appropriate number coded place on the simple line drawing black posterboard. As they begin pasting their handwritten expressions on the image, an image of Mike Brown will begin to take shape. With their hands students are reversioning Mike Brown, and the possibilities and potential that could have existed within his voice, had it not been taken away from him through white supremacist state sanctioned violence.

- Unpack and discuss: Once the image is completed, allow time for students to begin processing their reactions to seeing the image of Mike Brown. Use the following essential questions as a way to allow youth to begin synthesizing their broader takeaways related to the lesson: a) How do we create spaces to reimagine our lives in the face of uncertainty?; b) How are our lives impacted and/or informed by social and systemic inequality (e.g., white supremacy, sexism, racism, homophobia)?; c) Why do people seek hope and liberatory possibilities in the face of uncertainty and difficulty?; d) How can stories be utilized as sites of healing and resistance?; e) What is cultural reversioning and how does it function as the practice of freedom?

Looking Ahead: Future Justice Acts

Our future is not certain but it is certain that tomorrow is tomorrow and the struggle will still be a struggle, as previous generations can attest. From these generations we continue to gather, refine, and reversion our traditions and practices, to once again serve as weapons of resistance in the struggle against white supremacist state sanctioned violence. It is critical that we not only pass down these traditions and practices to youth, but that we enable them to envision their voices as powerful voices that offer additional layers of meaning on top of ancient and powerful knowledge bequeathed to us from our ancestors. In addition to working with youth to assist them in recognizing the power behind their voices, we must also encourage them to take action, and engage in the process of praxis.

In concluding this lesson, we encourage teachers and facilitators to co-create spaces in their classrooms and pose questions to foster the translation of critical thought into action with the aim of resisting white supremacist state sanctioned violence in their schools, neighborhoods, and communities.

Revisioning Organizer

THINKING: How do we teach/challenge Black Youth in ways that cultivate a critical consciousness in a productive and transformational fashion? How do we as leaders—scholars—activists—artists challenge Black youth to take up this work?

Draft verse rewrite: identify at least two lines you’d change to reflect the conversation you had about seeing/hearing.

Verse 1: Solange & Lil Wayne:

You got the light, count it all joy

You got the right to be mad

But when you carry it alone you find it only getting in the way They say you gotta let it go

Now tell ’em why you mad son

Cause doing it all ain’t enough

‘Cause everyone all in my cup

‘Cause such and such still owe me bucks

So I got the right to get bucked

But I try not to let it build up

I’m too high, I’m too better, too much

So I let it go, let it go, let it go

[Pre-Hook 1: Solange]

I ran into this girl, she said, “Why you always blaming?”

“Why you can’t just face it?” (Be mad, be mad, be mad)

“Why you always gotta be so mad?” (Be mad, be mad, be mad)

“Why you always talking ****, always be complaining?”

“Why you always gotta be, why you always gotta be so mad?” (Be mad, be mad, be mad)

I got a lot to be mad about (Be mad, be mad, be mad)

[Hook: Solange]

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love, baby?

[Verse 2: Lil Wayne]

Yeah, but I, got a lot to be mad about

Got a lot to be a man about

Got a lot to pop a xan aboutI used to rock hand-me-downs, and now I rock standing crowds

But it’s hard when you only

Got fans around and no fam around

And if they are, then their hands are out

And they pointing fingers

When I wear this **** burden on my back like a **** cap and gown

Then I walk up in the bank, pants sagging down

And I laugh at frowns, what they mad about?

Cause here come this **** with this mass account

That didn’t wear cap and gown

Are you mad ’cause the judge ain’t give me more time?

And when I attempted suicide, I didn’t die

I remember how mad I was on that day

Man, you gotta let it go before it get up in the way

Let it go, let it go

[Pre-Hook 2: Solange]

I ran into this girl, she said, “Why you always blaming?”

“Why you can’t just face it?”

“Why you always gotta be so mad?” (Be mad, be mad, be mad)

I got a lot to be mad about (Be mad, be mad, be mad)

[Hook: Solange & Both]

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love go?

Where’d your love, baby?

[Outro: Solange]

I ran into this girl, I said, “I’m tired of explaining.”

Man, this **** is draining

But I’m not really allowed to be mad

References

Alexander, M. (2012). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press.

Gilroy, P. (1993). The black Atlantic: Modernity and double consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hooks, B. (2004). We real cool: Black men and masculinity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Keyes, C.L. (2004). Rap music and street consciousness. Champaign, Il: University of Illinois Press.

[1] For more information regarding resources on white supremacy, racism, sexism, and homophobia, we recommend exploring the extensive resources available at http://www.tolerance.org/

From “I Have A Dream” to “I Dream of a World”: Steps to Creating a Sanctuary Classroom*

Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

Intended Audience: 1st-12th grades (lesson plan can be adapted for selected grade level)

Overview: Less than sixty years ago, our country operated under a system of legalized segregation and oppression. Schools were separate and unequal and we had two nations—one black and one white—one oppressed and the other free. Even though any challenge to the system was met with resistance there was a growing collective that was crying out for change and was willing to challenge and confront the system in both the courtroom and in political and social spaces. While lawyers like Thurgood Marshall, Constance Baker Motley, and Elaine Jones worked within the system to change the laws, Civil Rights leaders like Dorothy I. Height, Bayard Rustin, and Fannie Lou Hamer found ways to use their social power to mobilize people to work within their organizations to bring about change. While college students were sitting down at counters in North Carolina, high school students were sitting down in classrooms in Little Rock, Arkansas. And while nonviolent resistance was the battle plan for black and white foot soldiers throughout the South, unchecked violence, mass arrests, and murder were the primary responses of white Southern politicians and police officers.

America, chiefly in cities throughout the South, was separated and deeply divided. It was an extraordinary time where leadership was a burden and jail time, particularly during the Birmingham Children’s March, was seen as a rite of passage. From that tumultuous time, where black people were fighting to have their right to vote be protected, to today where a black man has now been elected twice to the highest office in our country, our American society has drastically changed — and some of our young people feel very disconnected from the historical events. In some ways, the question is not “How do we teach young people about the Civil Rights Movement” but rather “What do we teach young people about the Civil Rights Movement.” And, it is not “How do we tell them about the leaders from this time” but rather, “How do we let these leaders speak for themselves and tell their own stories.” In order for young people to fully connect with the past they need to be completely engaged with, and feel connected to, the stories. Students must learn that the stories of the past have shaped their present reality and are the tools by which they can create their future. We are now at this place again where we must teach young people about tolerance, about the importance of sharing and hearing all stories, and about the need for having a sanctuary classroom in which to do all of this. This lesson plan is designed to use Dr. King’s “I Have A Dream” speech to engage our students in a broader conversation about the need for a sanctuary classroom.

Scope and Sequence: The lesson begins with a broad contextualization of some of the key events that shaped the focus and planning of the March on Washington. Students will examine video(s), photos, and text to interpret the historical context of this time period. With this context in mind, students will then work together to create a Mission Statement for their sanctuary classroom.

Historical Thinking Standards (National Standards for U.S. History)

Standard 3: Historical Analysis and Interpretation

Common Core State Standards

English Language Arts Standards » History/Social Studies » Grade 6-8

English Language Arts Standards » History/Social Studies » Grade 9-10

English Language Arts Standards » History/Social Studies » Grade 11-12

Objectives

- Examine, analyze, and evaluate some of the key events that took place during the modern Civil Rights Movement.

- Review and synthesize Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

- Write and edit a sanctuary classroom Mission Statement to post in their classroom.

Essential Questions

- What was the important message behind the “I Have a Dream” speech?

- What is the importance of the sanctuary classroom?

- Why is it important to collectively write a sanctuary classroom Mission Statement?

Recommended Class Times: Although the support materials can be used to extend the teaching time up to 75 minutes, the lesson plan was designed for a 45-50 minute class period.

Lesson Structure: These lessons use the “close reading” teaching strategy and the Iceberg Theory, and are designed to help students clearly understand and fully engage with the content. The goal is to equip them with the foundational training that they need to participate in critical conversations about the material. Using these two strategies, students will enter into, and become engaged with, the content A(bove), B(eneath), and at the B(ottom) of the Water:

Step One: when students work “Above the Water,” teachers activate prior knowledge in an effort to determine what the students know about the modern Civil Rights Movement and about the leaders, what they understand about the March on Washington, the modern Civil Rights Movement, and what they have learned about the impact of the Movement on American history. At this level of engagement, teachers are focused on making sure that their students are actively thinking and working to connect this new information with their prior knowledge.

Step Two: when students work “Beneath the Water,” they are introduced to the readings, discussions, and primary sources about Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. It is at this level of engagement that students will work very closely with the material and teachers are then focused on helping students to examine, analyze, and understand this new material.

Step Three: once students reach the “Bottom of the Water,” they will begin to integrate, apply, expand upon, and demonstrate an understanding of the new material. Students will work together to create a list of values that can be used to write their joint Mission Statement for use in creating a sanctuary classroom. At this final level of engagement, teachers want to ensure that students have effectively infused this material into their knowledge bank.

Vocabulary

Each word includes the standard Merriam-Webster definition and a link to an example that demonstrates the word.

Boycott: to engage in a concerted refusal to have dealings with or do business with a person, store, organization to express disappointment or force a change in conditions.

In 1963, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, one of the first documented bus boycotts happened when the black citizens boycotted the bus system for eight days. Historians believed that this boycott inspired the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Civil Disobedience: During the Civil Rights Movement, civil disobedience was one of the primary methods of nonviolent resistance that was used to challenge racism and legalized segregation. It is an active refusal to obey certain laws, demands, and commands that support the system.

In April 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organized the Birmingham Campaign to protest racism and racial segregation. After being arrested and in response to a letter from white clergyman who suggested that outside leaders should not be involved in events happening in Birmingham, Dr. King, with the help of Rev. Wyatt T. Walker, released his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

Civil Liberties vs. Civil Rights: Often confused, our civil liberties and our civil rights are built upon one another but are not the same thing: our civil liberties grant us freedom from arbitrary governmental interference, specifically by denial of governmental power and in the United States especially as guaranteed by the Bill of Rights and our civil rights are the rights of personal liberty guaranteed to United States citizens by the 13th (abolished slavery) and 14th (provides equal protection under the law) Amendments to the Constitution and by acts of Congress.

Civil Rights Act of 1964: It is the nation’s benchmark civil rights legislation that prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin and effectively ended the system of legalized segregation that had been in place since the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case. Although President John F. Kennedy initially proposed the Act during the summer of 1963, it was actually pushed through Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon Baines Johnson, .

Civil Rights Movement: From 1954-1972, the modern Civil Rights Movement was a national political and social movement, designed to challenge and change the American system of legalized segregation. Using nonviolent forms of resistance, the campaign took places in various cities throughout the South, in social and public spaces, and in the courtroom.

Desegregate: to eliminate segregation in any law, provision, or practice requiring isolation of the members of a particular race in separate units.

In 1954, after a series of unsuccessful challenges to the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, the United States Supreme Court (USSC) ruled that legalized system of segregation in the school system was inherently unequal. One year later, the Court ruled that schools needed to integrate “with all deliberate speed.”

Racial Discrimination: the act of treating someone, an employee, an applicant, or a student, unfairly because they possess characteristics of a specific race, as in hair texture, skin color, facial features or they are married to someone who does. This is often confused with color discrimination, which only pertains to the color of a person’s skin.

Freedom Riders: Starting in May 1961, several civil rights activists, “the Freedom Riders,” rode interstate buses in segregated cities throughout the South to challenge the local and federal government’s decision not to enforce the Supreme Courts ruling in the Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) and the Boynton v. Virginia (1960) cases that segregated buses were unconstitutional. At almost stop, the Freedom Riders were attacked, beaten, and in some cases arrested.

Jim Crow Laws: At the end of the American Reconstruction (approximately 1876), a series of state and local laws were enacted across the country mandating and legalizing de jure segregation in all public facilities in the South. In the North, segregation was primarily de facto and happened in housing, bank lending practices, and in job discrimination.

Protest Marches: In addition to a series of local protest marches, the modern Civil Rights Movement held three large-scale marches on the Mall in Washington D.C.: the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, which is considered to be the first official large demonstration of African Americans; the 1963 March on Washington (Dr. King spoke at both of these marches); and, the 1970 Kent State/Cambodian Incursion Protest, which was held a week after the Kent State incident to protest both that and President Richard Nixon’s incursion into Cambodia.

Segregation: the separation or isolation of a race, class, or ethnic group by enforced or voluntary residence in a restricted area, by barriers to social intercourse, by separate educational facilities, or by other discriminatory means. Segregation has its roots in both the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sanford case, which ruled that since black Americans could not be citizens then they had no rights that whites were bound to respect, and the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, which ruled that separate facilities could be established for white and black Americans as long as they were equal.

Voting Rights Act of 1965: Less than one-year after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination in voting, into law. It extended and protects the rights guaranteed under the 15th Amendment, which prohibits the federal and state government from denying a citizen the right to vote.

Lesson Plan

Motivation

- (Time Permitting) Before students walk into the classroom, place a colored square on their desk, face down. Each square should have a different word written on it. Since the words should connect to the central theme, “We Dream of a Classroom With…”. Word choices could include: love, happiness, togetherness, sisterly love, brotherly love, admiration, all voices included, equality, justice, freedom, political power, safety, green spaces, clean air, safe spaces, dignity, respect, pride, opportunities, manifest digitization, peace, unity, YOU (“you” should be written on at least four-five of the cards).

Depending upon the grade level, teachers can also pass out the index cards (or construction paper) once students have gotten settled in their seat.

- Lecture Blast: Once students are seated, tell them that approximately fifty years ago (1963) on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, half a million black and white Americans came together in support of a dream: the dream of building and creating a better America. They had come from all over the country, in cars, on trains, on buses, and in some cases, on foot to bear witness and be present at this historic moment that fundamentally shaped our society. The Civil Rights Movement, as a whole, consisted of a series of moments that, when taken together, make up our American quilt.

Depending upon the grade level, either pass out the attached photos (Primary Source Package) or project images onto the screen.

- Tell them that they are going to examine Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech to talk about the power of collective agreement. They are going to do some critical thinking, close reading, open discussion and then create a paper quilt and develop a collective Mission Statement.

- Activate prior knowledge by asking students to share what they know about the Civil Rights Movement and Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Depending upon the grade level of your students, this can range from a few things to an entire list. If need be, once students reach seven-ten events, have them begin to define each of these moments. Use the time to clear up any misconceptions that students may have about these moments.

- After the class discussion, post the list of events where students can add to them. Have them read the following selection from Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech:

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Depending upon your classroom, students can either read the quotes or watch Dr. King’s speech.

- Once the students have finished reading (or listening to) the speech, have them take a moment to discuss whether or not they think we have achieved Dr. King’s dream. Have the students write their answers first, and then share them in either small groups or in a whole group discussion.

Class Discussion

- Tell the students to take a moment to think about what it means to have a “dream” and be willing to work hard for it. Ask them whether or not they have dreams and then have them think about the difference between an individual dream and a collective dream.

- Tell the students about the importance of collective agreement and that when people heard Dr. King’s speech, they were charged with trying to live out the creed and apply it in their own lives. Tell them they are going to do something similar so that they can transform their classroom into a sanctuary space.

- Outline for the students the reasons for, what a sanctuary classroom is, and why it is important to create one. Note the following key points:

- Sanctuary classrooms create a sense of safety and inclusion for all.

- They help to develop an understanding of what it means to seek sanctuary by dispelling negative myths and creating an open environment.

- They open up the space to provide for learning opportunities around human rights, social justice, diversity and interdependence.

- They are designed to increase student voice and agency, and to promote active citizenship.

- Ask them to think about the key points and add any other reasons why they think it is important.

Time permitting (and depending upon the grade level): have students watch Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Ted Talk on “The danger of a single story” and to explore why it is important to have a classroom where all voices are included.

Class Assignment

- Tell students that they are going to work together to outline the Mission Statement. Have them think about this and reflect (either on paper or out loud) on why this is important.

- Working collectively, students should develop a list of values related to your classroom space (limit to five).

- Depending upon your classroom, they can either work together to transform the list of values into a Mission Statement or you can create it for them.

- Once completed, post the Mission Statement in your classroom and make a copy of it for each student. Ask each student to take it home, think about it, and then be prepared to sign it (if they agree with what is written).

- Moving forward, students should be told that every time the Mission Statement is violated, they must come back together and discuss the key points and then agree on them again (or adjust them, if need be).

Wrap-Up

- Students should then be instructed to turn over their post cards and finish the sentence. Depending upon their grade level: they can either share their word out loud and place it on the board to build a Collective “We Dream of a Classroom . . . ” Postcard Quilt Or take a moment to reflect on it in their journal and then share and add to the classroom Quilt.

Homework

- Depending upon the grade level, students can watch the entire “I Have a Dream Speech” and think about their Mission Statement and whether anything should be added to it. For younger students, they should be encouraged to share their Mission Statements with their parents for discussion and engagement.

Selected Bibliography

Articles

Cowan, Jane K. “Culture and Rights after “Culture and Rights“” American Anthropologist 108 (2006): 9-24. JSTOR.

Gaines, Kevin. “The Civil Rights Movement in World Perspective.” OAH Magazine of History 21 (2007): 57-64. JSTOR.

Hill, Walter B., Jr. “Researching Civil Rights History in the 21st Century.” The Journal of African American History 93 (2008): 94-99. JSTOR. Web. 23 Sept. 2013.

Jalata, Asafa. “Revisiting the Black Struggle: Lessons for the 21st Century.” Journal of Black Studies 33 (2002): 86-116. JSTOR.

Books

A Testament of Hope: the Essential Writing of Martin Luther King, Jr. Edited by James M. Washington. San Francisco: Harper, 1990.

Bennett, Lerone Jr. Great Moments in Black History: Wade in the Water. Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, Inc., 1979.

Davis, Townsend. Weary Feet, Rested Souls, A Guided History of the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Norton, 1999.

The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader: Documents, Speeches, and Firsthand Accounts from the Black Freedom Struggle, 1954-1990. Edited by Clayborne Carson, David J. Garrow, Gerald Gill, Vincent Harding, and Darlene Clark Hine. New York: Viking, 1991.

Websites:

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

US Department of Health and Human Services

Photographs:

Images from the March on Washington, 1963

*A version of this lesson plan was originally prepared for both McDonogh School and the Black Quilted Narratives program. It is reprinted here with permission from the author.

Exploring the Reasons Why Trump Won

Gloria Ladson-Billings, Ph.D.

Intended Audience: Middle and High School Students

Objectives: Students will have an opportunity to examine the explanations for why Donald Trump won the 2016 Presidential election despite almost universal predictions that he would not and they will examine “patterns” of US presidential choices.

Historical Thinking Standards (National Standards for U.S. History)

Standard 3: Historical Analysis and Interpretation

Common Core State Standards

English Language Arts Standards » History/Social Studies » Grade 11-12

Materials:

1. Copy of Article II, Section I of the US Constitution (the qualifications for President)

2. Background information on US Presidents – Andrew Jackson, Woodrow Wilson, and George Herbert Walker Bush.

Lesson Plan

Introduction

Begin with this question: “What does the US Constitution say about who is eligible to be President?”

1. Determine what students already know about qualifications.

2. Share wording from Article 2, Section 1 of the US Constitution:

No person except a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States, at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that office who shall not have attained to the age of thirty-five years, and been fourteen years a resident within the United States.

3. Ask students what they think about the qualifications.

4. Ask student to share what “other” qualifications they notice about all of the people who have previously held the office (gender, social class, education, wealth, previous experience).

5. Ask students: “Raise your hand if you thought Donald Trump would win the 2016 election?”

6. Ask students to share their reasons why they thought he would win. (If none of the students raised their hands—indicating they all thought Hillary Clinton would win—then proceed with question as to why they thought he won.

7. List the reasons that students offer for why they thought Trump won the election.

8. Go back through their reasons and ask students to provide evidence for their reasoning (specifically asking, if need be, where is the data?).

Part 2 – Examining Prevailing Explanations

1. Tell the students that the two candidates (Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, depending upon your students and where you are located, you can expand to include Third Party candidates) had two different perspectives on the United States. Clinton’s campaign theme was “Stronger Together” and Trump’s campaign theme was “Make America Great Again.” Ask students to discuss what each theme was trying to say about the country.

2. Ask them to think about which themes spoke to which voters? Why?

3. Ask students to break into groups of three and build a rationale for Trump’s win based on the following perspectives:

Trump won because America was not ready to elect a woman as president of the United States.

Trump won because working class people were tired of being “left out.”

Trump won because he played on the racism of White voters.

After hearing all of the rationales, have them decide as a class which one seems most compelling? And why?

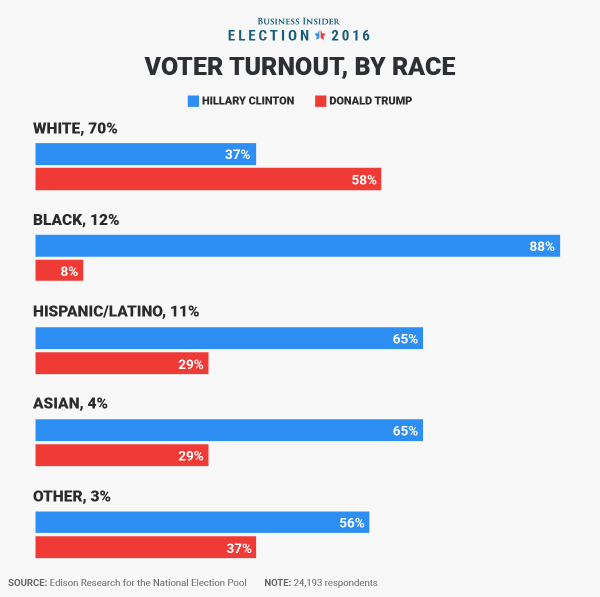

Give students the following racial demographic information:

Ask students to explain the chart and answer, what does it say about how certain groups of African Americans feel about Trump as president?

Part 3 – Wrap Up

1. How have other Presidents used race as a way to appeal to specific constituents? Give students these examples:

Andrew Jackson – The Indian Killer (“Trail of Tears”)

Woodrow Wilson – Attitudes toward race (“Birth of a Nation”)

George Herbert Walker Bush – Willie Horton Ad

2. Ask students to work with a partner to come up with a campaign ad to the following constituents. Develop a campaign theme and three campaign promises that will appeal to the following groups:

Working class Whites

Men

African Americans

Latinos

Share the campaign ads.

Suggested Readings

http://www.ew.com/article/2016/11/09/michael-moore-trumpland

http://www.latimes.com/politics/la-me-blacks-fear-trump-20161129-story.html

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/21/race-relations-following-trumps-election/

Exploring the (New) Political Climate

Nadiera Young

Intended Audience: Middle School Students

OBJECTIVE: While continuing to learn to establish a classroom for healthy discussions, students will create their own version of a “good” society by collaborating with peers and answering big questions. This lesson plan is designed to help students understand that conversations surrounding politics, race, religion, etc. can happen in respectful ways and that each person is different, but these differences should not be used to put others down for the benefit of those in power.

Cross Curricular

- Science: Students will learn about the 2016 presidential candidates’ stances on Global warming and climate change, to help determine what they hope to see in a potential president.

- Social Studies: Students will learn about how America became a two party system (majority) to better understand what it means to be a Democrat and Republican, and also understand that while these are the main two systems they are not the only ones.

- Math: Students will learn about the Electoral College, the role it plays in our voting system, and what role the single vote of a person plays in electing the President of the United States.

- Language Arts: Students will learn how to have discussion on difficult/fragile topics such as the 2016 Election, learn how to speak constructively and with evidence to support their opinions, and to do so in a respectful manner.

Cultural Connection

Students will understand that conversations surrounding politics, race, religion, etc. can happen in respectful ways. Each person is different, but these differences should not be used to put others down for the benefit of those in power.

Character Connection

Students will understand that when they listen to others, really listen and engage in meaningful conversations, they may be able to see things from multiple perspectives or perspectives that others may not be able to see.

Lesson Plan

Welcome/Purpose/Hook: How will I connect this concept to students’ lives or to other content that we have learned?

Drill (15 mins)

Students will define Safe Space and Brave Space to determine what they hope to see their classroom form into.

Options of answering the question:

1. Writing on a sticky note

2. Interpretive movement

3. Speak the answer out loud

Mini Lesson (8 mins)

Details of Lesson Sequence

How did we get here? ~Political Climate in the US

· What is polarization? ~Refers to the division of political parties along ideological lines and movement away from the political center (not a constant feature of American democracy).

· Ideology: the body of doctrine, myth, belief, etc., that guides an individual, social movement, institution, class, or large group.

· How does this impact how we have discussions today?

Guided Practice (15 mins)

Class Discussion

Students will create their ideal society.

· What is a good society?

· How should we get it?

· What are the causes of the problems we see today?

Modeling- When I think of a good society, I consider the following things:

· Who is impacted by my decisions? How?

· My feelings

· Others’ feelings

· Multiple lenses to consider multiple perspectives

· Think past myself/my own world

Checks for Understanding (5 mins)

I will start the discussion by posing a question. Students will contribute to the question by discussing answers with peers, challenging peer, asking for clarification, and helping peers when they are unable to articulate thoughts. I will gauge understanding through the answers presented in the discussion.

I will know students are applying what they have learned by how well the discussion goes. Students should use ground rules when engaged in the discussion.

Independent Practice (15 mins)

In small groups, students will create their perfect society. Students can create this society in their own image, without parameters. Students will need to show this using images or words

Evaluation/ Final Checking for Understanding and Closure (10 mins)

Can all people be included in a society even if they do not agree with everything that is being said or done?

| . | ||

|

|

||

America is A Divided Nation: Singing the Post-Trump Blues

Trump Syllabus K12: Lesson Plans for Teaching During the New Age of Resistance (#TrumpSyllabusK12)

created & compiled by Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

with Alicia Moore, Ph.D. & Regina Lewis, Ph.D.

Lesson Plans for Teaching During this New Age of Resistance (#TrumpSyllabusK12)

#TrumpSyllabusK12 is a compilation of lesson plans written by and for K-12th grade teachers (and college educators) for teaching about the 2016 presidential campaign; about resistance and revolution; about white privilege and white supremacy; about state-sanctioned violence and sanctuary classrooms; about fake news and Facebook; and, about freedom and justice. It is designed to transform our classrooms into liberated nonsexist nonmisogynistic anti-racist anti-classist spaces without any boundaries or borders. It is meant to liberate and free our students by providing them with lesson plans to challenge them to become global critical thinkers. We invite you to join with us as we actively work to push back against the establishment of this New World Order and we draw our line in the sand and work to liberate and change the world, one student at a time.

Each lesson plan is presented in its entirety and includes Warm Up and Group Activities, Essential Questions and Objectives, Resources, an Essay or an Overview, and they connect directly to the Common Core Standards for Math, History, or Language Arts; and, to the National Council of Social Studies Standards.

Please note that lesson plans are still being accepted at griotonthego@gmail.com and are being added daily.

(ES=Elementary School; MS=Middle School; HS=High School)

######

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Opinion Editorial: America is a Divided Nation

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

2. Tips for Facilitating Classroom Discussions on Sensitive Topics

-Alicia Moore, Ph.D., and Molly Deshaies

SECTION ONE: EXAMINING CAMPAIGN 2016

3. The Electoral College vs The Popular Vote: Who Should Choose OUR President? (HS)

-Jocelyn Thomas

4. Exploring the (New) Political Climate (MS)

-Nadiera Young

5. Exploring the Reasons Why Trump Won (MS/HS)

-Gloria Ladson-Billings, Ph.D.

6. Exploring the Fake News Cycle (MS)

-Baba Ayinde Olumiji

7. Using Photographs to Explore Differing Political Perspectives (ES)

-Alicia Moore, Ph.D., and Angela Davis Johnson

8. Trump and Gender Bias, By the Numbers (HS)

-Kelly Cross Ph.D.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES (POETRY):

9. Oya for President (to be read OutLoud)

-Alexis Pauline Gumbs

10. Mourning in America: A Black Woman’s Blues Song

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

SECTION TWO: POLITICS IN THE “POST-TRUMP” NARRATIVE

11. Harassment and Intimidation in the Aftermath of the Trump Election: What Do We Do Now? (MS/HS)

-Sarah Militz-Frielink and Isabel Nunez, Ph.D.

12. From “I Have A Dream” to “I Dream of a World”: Steps to Creating a Sanctuary Classroom (All Grades)

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

13. Hope, Action, & Freedom in the Times of Uncertainty (HS)

-Conra D. Gist,Ph.D., Angela Davis Johnson, & Tyson E.J. Marsh, Ph.D.

14. Writing White Privilege, Race, and Citizenship: Reading Angela Davis, Toni Morrison, Claudia Rankine, and Walt Whitman (HS)

-Ileana Jiménez

15. A Pedagogy of Resistance in the Struggle Against White Supremacist State-Sanctioned Violence* (MS/HS)

-Tyson E.J. Marsh, Ph.D.

16. Lessons in Black Feminist Criminology: Disrupting State and Sexualized Violence Against Women and Girls #GrabtheEmpowerment (HS)

-Nishaun T. Battle, Ph.D.

17. Giving Voice & Making Space: Dismantling the Education Industrial Complex in an Effort to Free Our Black Girls* (MS/HS)

-Aja Reynolds & Stephanie Hicks

18. Exploring the “Crisis” in Black Education from a Post-White Orientation* (MS/HS)

-Marcus Croom

19. The African American Saga: From Enslavement to Life in a Color-Blind Society (Or Racism Without Race)*(HS)

-Yolanda Abel, Ed.D., and LeRoy Johnson

20. #Evolution or Revolution: Exploring Social Media through Revelations of Familiarity* (HS)

-Kimberly Edwards-Underwood, Ph.D.

21. Replace Fear with Curiosity: Using Photographs and Poetry to Process Election 2016 (ES)

-Tracy Kent-Gload

22. #WeGotNext: Black Youth Activism and the Rise of #BlackLivesMatter* (HS/MS) **NEW**

-Sekou Franklin

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

23. Steps to Combating Anti-Muslim Bullying in Schools

-Mariam Durani, Ph.D.

24. #ClintonSyllabus 1.0

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D., Alicia Moore, Ph.D., Regina Lewis, Ph.D.

25. Book: Black Lives Matter (Special Reports)

–

*The following lesson plans were originally published in the Association for the Study of African American Life & History’s Black History Bulletin and are reprinted here by permission of the authors.

October 19, 2016

by Karsonya “Kaye” Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

(Originally published here http://www.mdhumanities.org/2016/10/a-writer-with-writers-connecting-the-roots-of-activism-from-new-york-to-baltimore/ )

Cover: “The New York Young Lords and the Struggle for Liberation”

The goal of the A Writer with Writers blog series is to interview interesting and engaging authors and explore the ways in which they use their pen and paper to think about some of the issues with which our country is struggling. My questions range from defining democracy to defining liberation; from analyzing the strength of community organizing to finding ways to bend our privilege to make substantive changes; from understanding the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement to measuring the ongoing impact of the Black Lives Matter social movement.

This month, in celebration of National Hispanic Heritage Month and in an effort to continue our conversations about protest and community engagement, I sat down with Dr. Darrel Wanzer-Serrano to talk about his latest book, The New York Young Lords and the Struggle for Liberation.

Kaye Whitehead: Your book seems to have some good parallels to Baltimore’s current uprising. How do you see your book connecting to our city?

Darrel Wanzer-Serrano: I think that one of the great lessons of the Young Lords (and they are, by no means, the only group of the era to offer this lesson) is to never underestimate the ability of a group of young people to change things. Young folks are at the cutting edge of new communication practices and technologies, they’re at the forefront of new ideas operating on the ground, and they have their pulse on the communities in which they reside. Another connection is something I write about most explicitly in the intro and conclusion: community control. As in Baltimore today and in other eras, the Young Lords demanded that communities have some level of control over institutions and land, that the people must have a say in the decisions that impact their daily lives. Finally, I think there’s something to the connections between racism, sexism, and capitalism that the Young Lords so aptly diagnosed in their time—something that can be helpful in explaining the conditions that gave rise to the recent Baltimore Rebellion.

KW: Who are some of your greatest writing influences?

DWS: Most, but not all, of my influences come from the other scholars that I read, and that list is constantly shifting. I love the way that my grad school mentor, John Louis Lucaites, writes his endnotes. I’m drawn to the complexity of folks like Chela Sandoval, whose Methodology of the Oppressed is a marvel of decolonial[1] feminist scholarship. I’m drawn to the imaginative interplay between content and form in the work of Gloria Anzaldúa and other decolonial feminist scholars and artists.

KW: What does being a writer mean to you?

DWS: To me, being a writer means that I am enacting a set of commitments to social responsibility with/to various real and imagined audiences. Writing emerges from my own embodiment and geo-political locatedness, which is something that I feel compelled to recognize explicitly in my written work. Being a writer who is a critical rhetorician, I see my task as fundamentally persuasive in the sense that I’m trying to get my readers to understand some aspect(s) of the world differently than they had before.

KW: Are there any subjects that you find it difficult to write about? Why?

DWS: I’ve been having a hard time writing about how to challenge racism(s). (Don’t get me wrong—I think writing about the histories of racism and anti-racist struggle, as complicated and complex as they might be, is relatively straightforward.) When I think about how to get my predominantly white, Midwestern students to commit to anti-racist struggle, I am more prone to draw blanks. This isn’t a writing problem, per se; rather, it’s more of a conceptual problem of how to efficiently and comprehensively (a paradox, to be sure) make the case to young white people who lack a vocabulary for talking about race and racism in public.

KW: In honor of National Hispanic Heritage Month, what are some books that you would recommend that elucidate the Hispanic culture?

DWS: The first is the second edition of Juan Gonzalez’s Harvest of Empire. It’s probably my favorite history of the Latino/a experience in the US. Gonzalez (a former Young Lord) is a wonderful writer and does a marvelous job weaving together Latino/a historiography, primary sources, and oral histories to tell the complex story of how Latino/a people came to be. The second is Raquel Cepeda’s Bird of Paradise, which is a memoir that tells the tale of her troubled childhood and coming-to-be as her own self. She engages complex issues of Latino/a history and anti-blackness, along with her own journey of personal https://www.facebook.com/MdCenterfortheBook/photos/a.372326269506650.88411.160985633974049/1198910530181549/?type=3discovery as she traces her ancestral roots.

[1] Decolonial: relating to the act of getting rid of colonization, or freeing a country from being dependent on another country

About the Author: Darrel Wanzer-Serrano, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Public Advocacy in the Department of Communication Studies, and founding member of the Latino/a Studies Minor Advisory Board, at The University of Iowa. He is a critical rhetorical historian whose research is focused on the intersections of race, ethnicity, and public discourse, particularly as they relate to formations of coloniality and decoloniality in the United States and within Latino/a contexts. Follow Dr. Wanzer-Serrano on Twitter or Facebook.

About the Interviewer: Karsonya “Kaye” Wise Whitehead, Ph.D. is Associate Professor, Department of Communication at Loyola University Maryland and the Founding Executive Director at The Emilie Frances Davis Center for Education, Research, and Culture. She is creator of the #SayHerName Syllabus. Her new anthology, RaceBrave, was published in March 2016.

“Sexual Assault: An American Pastime” (Baltimore Sun OpEd)