#WeGotNext: Black Youth Activism and the Rise of #BlackLivesMatter*

Sekou Franklin

Intended Audience: Middle School And/Or High School

Overview: Through collaborative exercises, students will learn about the origins and activities of student/youth-based formations during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Students will specifically learn how young people propelled racial and economic justice movements in the 1930s, the civil rights and black power movements in the 1960s and 1970s, the anti-apartheid in the 1980s, anti-poverty and anti-violence initiatives in the 1990s, and the Movement for Black Lives Matter in the twenty-first century.

Students will also understand the important role of movement bridge-builders in youth-based movements, as well as investigate how the make-up of movement infrastructures (the type of organizations, resources of activists, intergenerational relations, collaborations between activist networks) shape the direction of black youth activism. Students will learn how black youth have developed creative organizing strategies to elevate the political status of youth in social movement campaigns. In addition, students will assess the political context or environmental conditions that shaped black youth activism during different time periods. Students will also learn about the various organizations that coordinated black youth participation.

National Council for Social Studies/College, Career, & Civic Life C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards[1]

- Enable learners to develop the capacity to know, analyze, and explain how young people can effect change

- Prepare students with critical thinking, problem solving, and collaborative skills needed for social change

- Help students learn to work individually and together as citizens

Dimension 2, Participation and Deliberation

D2.Civ.8.9-12—Evaluate social and political systems in different contexts, times, and places that promotes civic virtues and enact democratic principles.

D2.Civ.9.9-12—Use appropriate deliberative processes in multiple settings.

D2.Civ.10.9-12—Analyze the impact and the appropriate roles of personal interests on the application of civic virtues, democratic principles, constitutional rights, and human rights.

TEACHING RESOURCES

Teachers are encouraged to review the following resources in preparation for teaching the lesson plan.

Internet Sources

Burke, Lauren Victoria Burke. “March2Justice Brings Fight Against Police Brutality to US Capitol.”

Day, Elizabeth. “#BlackLivesMatter: The Birth of a New Civil Rights Movement,” The Guardian.

Gruzen, Tara. “Unions Get New Breed of Activists: College Students Seeking to Boost Labor Movement.”

Juanita Jackson Mitchell, Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series)

The King Center, “Six Steps of Nonviolent Social Change.”

North Carolina A & T University Student Newspaper Collection

Pierre-Louis, Kendra. “The Women Behind Black Lives Matter.”

Southern Negro Youth Congress (1937-1949)

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Legacy Project

Videos

Black Youth Project 100, “Building a Movement #WeReadyWeComing.”

Dream Defenders, “Dream Defenders Take Over Florida For Trayvon Martin”

Esther Cooper Jackson at 96, The Laura Flanders Show.

Freedom Rides, “The Student Leader” Excerpt, PBS.

Rainbow/Push “Solutions to Urban Violence” Conference, C-SPAN.

SNCC’s Legacy: A Civil Right’s History, CNN.

LESSON PLAN

Goals of Lesson Plan: This lesson plan aims to guide students through the different forms of black youth activism, both chronologically from the 1930s to the twenty-first century, and, organizationally as students will evaluate the importance that grassroots organizations and infrastructures play in coordinating youth-based activities. The lesson plan is designed to take up to three class periods but can be shortened.

Warm-Up Activity (40 Minutes):

Have the class discuss the reading about black youth activism. The discussion should focus on the factors that shaped the social and political consciousness of black youth from the 1930s to the twenty-first century.

- Describe the political context or setting that shaped the consciousness or attitudes of the organizations.

- Describe the key figures (e.g. Mary McLeod Bethune, Ella Baker, the Black Lives Matter activists) or movement bridge-builders who cultivated young activists during their respective time periods.

- Explain why the type of organizations or networks—what is referred to as movement infrastructures—are important to expanding opportunities for young people to participate in grassroots activism

Activity #1 (1 hour and 40 Minutes):

After the warm-up activity, divide the class into four groups designated by a specific time period: 1930s-1940s, 1950s-1970s, 1980s-1990s, and the 2000s. Each group is advised to review the supplemental materials (see below) that expand upon the required reading about black youth activism. The materials provide concrete details of the strategies, tactics, motives, demands, and the socio-economic and political conditions of each time period. The groups will be given 40 minutes to review the materials, answer the guided questions and complete the graphic organizer for the time period. After the activity, each group will have 15 minutes (a total of one hour) to present their findings to the entire class.

Group I: 1930s-1940s

Supplemental Materials

- Juanita Jackson Mitchell, the most prominent youth activist in the NAACP

- Southern Negro Youth Congress

- Watch an excerpt of an interview with Esther Cooper Jackson of the Southern Negro Youth Congress (watch 2:00-5:00 mark).

Guided Questions

- Why did Juanita Jackson Mitchell get involved with the NAACP?

- Why did Esther Cooper Jackson join the Southern Negro Youth Congress?

- What initiatives were carried out by both the NAACP Youth Council and the Southern Negro Youth Congress?

FIGURE ONE: Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC)

Group II: 1960s-1970s

Supplemental Materials

- Watch an excerpt of the students involved in the Nashville students and the 1961 Freedom Rides (4:37 minutes).

- Watch videos: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Student Organization for Black Unity: The A & T Register newspaper

Supplemental Materials

- What were some of the challenges facing the students who joined the Freedom Rides of 1961?

- What were the goals and objectives of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Student Organization for Black Unity?

- Who were some of the key leaders or movement bridge-builders that helped to coordinate the Freedom Rides as well as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Student Organization for Black Unity?

FIGURE TWO: Freedom Riders, 1961

Group III: 1980s-1990s

Supplemental Materials

- Free South Africa Movement/Student Divestment Movement: Associated Press. AFL-CIO’s “Union Summer” labor initiative

- Watch excerpt of Errol James of the Black Student Leadership Network at the Rainbow/Push “Solutions to Urban Violence” conference (2:15:58-2:21:25 mark).

Guided Questions

- What were the main concerns of students involved in the Free South Africa Movement/Student Divestment Movement?

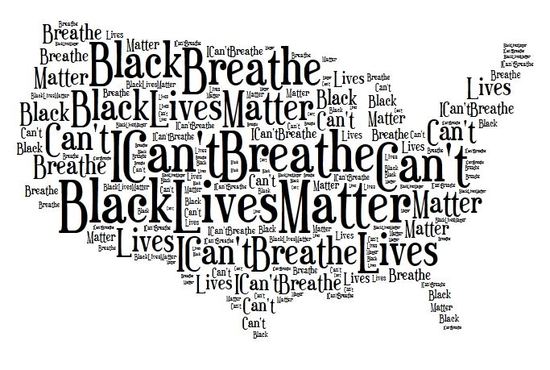

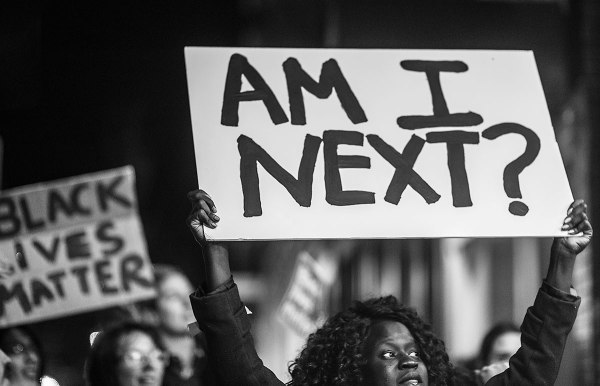

FIGURE THREE: Scenes from #BlackLivesMatter

Group IV: 2000s (Movement for Black Lives Matter)

Supplemental Materials

- Black Lives Matter, The Guardian.

- Women in the Movement for Black Lives Matter, In These Times.

- Watch Black Youth Project 100, “Building a Movement #WeReadyWeComing“

- Watch Dream Defenders, “Dream Defenders Take Over Florida For Trayvon Martin”

Guided Questions

- What are the goals and objectives of the Black Lives Matter organization and the broader Movement for Black Lives Matter?

- How has the Movement for Black Lives Matter given youth, women, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people opportunities to participate in social movements?

- What have been some of the initiatives carried out by organizations such as the Black Youth Project 100 and Dream Defenders, which are groups that affiliate with the broader Movement for Black Lives Matter?

- Based on the excerpt of the Black Student Leadership Network (see required reading) and the video of the “Solutions to Urban Violence,” what were the organization’s goals, strategies and tactics?

- What are the similarities and differences between the Black Student Leadership Network (see required reading) and the AFL-CIO’s Union Summer program?

FIGURE FOUR: Scenes from #BlackLivesMatter

Conclusion

This lesson plan has two objectives. First, it informs students and community leaders of the importance and diversity of youth-based (students, youth, young adult) initiatives that challenged injustices and inequalities. The participants will learn that youth activism is central to black politics, both historically and contemporary, and is constitutive of American politics. Secondly, the participants will understand how to build democratically-oriented social movements. They will discover that movement-building initiatives is a co-learning process between activists and the communities or constituents they are trying to organize for social change. Thus, this lesson plan allows the participants to learn about youth-based movements and to develop their own capacity as social justice leaders.

[1]. National Council for the Social Studies, The College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History, Accessed on November 15, 2015.

Background Information

BLACK YOUTH AT THE FOREFRONT OF SOCIAL MOVEMENT ACTIVISM

Since the early twentieth century, young people have been instrumental in shaping American political culture and the social and political life of African Americans.[i] From the NAACP Youth Council and the Southern Negro Youth Congress in the 1930s and 1940s to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Student Organization for Black Unity in the 1960s and 1970s, young people were the frontline activists during the two major protest waves of the twentieth century. Young blacks then helped to propel the Pan-African and black feminist movements of the 1970s, as well as the Free South Africa Movement/Student Divestment Movement of the 1980s. The Black Student Leadership Network was another group that set up dozens of freedom schools in low-income communities during the first half of the 1990s. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, young people affiliated with the Movement for Black Lives Matter protested racialized violence and police killings of African Americans.

This essay provides an overview of black youth activism from the 1930s to the twenty-first century. It gives special attention to four periods of black youth activism: black youth radicalism from the 1930s-1940s; the modern civil rights and black power movements between the 1950s-1970s; the anti-apartheid movement of the 1980s, followed by Black Student Leadership Network and other youth-oriented movements; and grassroots youth activism in the twenty-first century such as the Movement for Black Lives Matter.

Black Youth Activism in the 1930s-1940s

The Great Depression politicized black youth and their adult allies in the 1930s. Mary McLeod Bethune, the director of the Negro Division of the National Youth Administration, drew attention to the Great Depression’s impact on black youth. In 1937, she sent a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt stating that while the United States “opens the door of opportunity to the youth of the world,” it slams it shut in the faces of its Negro citizenry.”[ii] In the late 1930s, she organized the National Conference on Problems of the Negro and Negro Youth and the National Conference of Negro Youth. The American Council on Education’s American Youth Commission also sponsored series of studies on black youth in the Depression Era. The studies found that poverty and racism of the period deepened the alienation of young blacks.[iii]

Thus, the 1930s experienced an upsurge of black youth militancy as demonstrated with the establishment of the NAACP Youth Council and the Southern Negro Youth Congress. Even before the creation of the NAACP Youth Council in 1936, black students in the 1920s revolted against the conservative leadership of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).[iv] In the early 1930s, young activists volunteered in local campaigns coordinated by the NAACP and other groups. In New York, civil rights activist Ella Baker teamed with George Schuyler[v] to form a youth economic cooperative called the Young Negro Cooperative League in response to the economic crises of the Great Depression. Also, black and white youth organizations in New York, assisted by the NAACP, formed the United Youth Committee in order to rally support for the National Labor Relations Act and an anti-lynching bill in Congress.

Juanita Jackson, the first national youth director of the NAACP Youth Council, was one of the most influential young activists of the 1930s. Historian Thomas Bynum writes that as director, “She believed that black youth, in particular, should be at the forefront of [the civil rights] struggle and have its voice heard in improving its own plight.”[vi] Prior to the appointment, she was involved in the City-Wide Young People’s Forum (CWYPF) in Baltimore, Maryland. The group assisted NAACP activist, Clarence Mitchell, with racial desegregation campaigns, and mobilized Baltimore’s black youth around a “Buy Where You Can Work” campaign that targeted local department stores.[vii]

The Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) was the most radical youth organization of the 1930s and 1940s. In 1937, the SNYC assisted 5,000 black tobacco workers in Richmond, Virginia who went on strike and formed the Tobacco Stemmers and Laborers Industrial Union. It then organized labor youth clubs, labor and citizenship schools in cities such as Nashville, Tennessee, New Orleans, Louisiana, Birmingham and Fairfield, Alabama.

In addition, SNYC activists advocated for voting rights such as the Right to Vote Campaign in 1940, as well as issued reports that publicized racial violence. SNYC affiliates set up committees to pay the poll taxes levied against southern blacks and organized the Abolish the Poll Tax Week in 1941.[viii] Another SNYC initiative was the development of youth legislatures in Alabama and South Carolina that outlined positions on labor policy, foreign affairs, and voting rights.

The SNYC eventually collapsed because of organizational fatigue and after it was targeted for political repression during the early years of the Cold War. By the end of World War II, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) initiated a secret surveillance campaign of SNYC affiliates in a dozen cities.[ix] Additionally, the SNYC had to answer repeated claims by the House Un-American Activities (HUAC) in Congress if it was a Communist-front organization.[x]

Black Youth Activism after World War II

The post-World War II generation grew up under different circumstances than those young people of the 1930s. The social and political consciousness of the activist generation were shaped by the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954; Emmett Till’s murder by Mississippi segregationists in 1955; the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955/1956; the Youth Marches for Integrated Schools; and the Little Rock desegregation campaign in 1957. Cold War politics further altered the landscape as political elites became increasingly concerned about the negative portrayal of race and American democracy within the larger international arena.[xi]

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) is considered the most important student/youth-based formation of the post-World War II era. It emerged in the aftermath of the 1960 student sit-in movement that encapsulated the South. Ella Baker, who was then on the staff of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, urged the organization and other allies to sponsor the Southwide Leadership Conference. Out of this conference, student leaders organized a temporary organization that was later called SNCC.

During its first five years, SNCC concentrated much of its activities on eliminating racial desegregation and voter disenfranchisement. In addition to its participation in the freedom rides, the youth group set up freedom schools and initiated community-organizing campaigns in the rural South beset by racial terrorism. In fact, it was common for SNCC members to immerse themselves in a community for a couple of years and organize, while simultaneously, urging local residents to shape the programs that were relevant to that particular community. SNCC’s philosophy, as Baker noted, was “through the long route, almost, of actually organizing people in small groups and parlaying those into larger groups.”[xii] According to Bob Moses and Charlie Cobb, both former SNCC activists, SNCC’s organizing approach “meant that an organizer had to utilize everyday issues of the community and frame them for the maximum benefit of the community.”[xiii] This strategy allowed SNCC to expand its membership beyond the ranks of student and youth members. It created a pathway for incorporating older and poorer constituents into the organization. In the late 1960s, SNCC also attempted to build alliances with the Black Panther Party and the National Black Liberators. Though these efforts failed, they represented the types of creative organizing strategies that SNCC experimented with during its years of operation.

The Student Organization for Black Unity (SOBU) was a youth-based formation that was founded in 1969 in Greensboro, North Carolina. The group had close ties to local networks and institutions such as the Greensboro Association of Poor People (GAPP), Malcolm X Liberation University, Foundation for Community Development, and youth activists from North Carolina A & T University. SOBU’s signature initiative occurred in 1969 when it assisted the protest efforts of students from Greensboro’s Dudley High School.

SOBU’s energies were dedicated to organizing high school and college students; building alliances with prisoners; working on black political parties such as the Black Peoples’ Union Party of North Carolina; implementing survival programs in impoverished communities; and establishing clothing centers, food-buying clubs, and community service centers. These activities were amplified in SOBU’s bi-monthly newspaper, The African World, which had a circulation of 10,000 people.

The most important years for SOBU occurred between 1971 and 1972 when it sponsored several regional conferences with the purpose of building a national Pan-African student and youth movement. It started local affiliates in New Haven, Connecticut; Houston, Texas; Kansas City, Kansas; Omaha, Nebraska; Denver, Colorado; and in a dozen other cities. After merging with the Youth Organization for Black Unity (YOBU), the group launched a campaign to save black colleges and universities from being “reorganized” and eliminated.

Despite the emergence of black power and groups such as SOBU, youth activism waned in the 1970s. SOBU collapsed in 1975 and the Black Panther Party’s influenced declined by the late 1970s. Young activists were the targets of political repression, most notably surveillance and infiltration by the FBI and COINTELPRO. The elections of Richard Nixon in 1968 and 1972 signaled a conservative resurgence that culminated with the ascendancy of Ronald Reagan as president in the 1980s.

Furthermore, the decline of black youth militancy was partially due to the victories of the civil rights movement such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. These victories expanded opportunities for members of the post-civil rights generation to articulate their grievances in the voting booth in ways not experienced by previous generations of African Americans. They also led to the development of a new black political class as indicative of the growth of black elected officials by 640 percent between 1970 and 2000. Yet as political scientist Robert C. Smith asserted in his acclaimed work We Have No Leaders: African Americans in the Post-Civil Rights Era, the resources and energy of black politics shifted away from popular mobilization initiatives that were central to black youth activism to institutionalized politics and other forms of elite mobilization.[xiv]

The post-civil rights generation became increasing fragmented along socioeconomic lines. While a thriving black middle-class was situated at one end of the spectrum, a significant portion of African Americans lived in America’s ghettos and was most harshly affected by public health epidemics.[xv] Indicative of these epidemics were the proliferation of crack cocaine, the spread of AIDS, gun violence, and high incarceration rates. For example, 20 percent of blacks born from 1965-1969 – the years immediately following the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 – were likely to have served time in prison by their early thirties. This trend far outpaced black men who came of age during the civil rights movement, as 10.6 percent born from 1945-1949 were likely to have been incarcerated by their early thirties. Overall, the black male incarceration rate was six times higher than white men born during the early stage of the post-civil rights era.[xvi]

Youth Activism and the Post-Civil Rights Generation

Even though popular mobilization declined after the mid-1970s, the post-civil rights generation spawned new youth-based movements and organizations that targeted racial, economic and social injustices. In the mid-1980s, students of color and progressive whites organized protests on college campuses against apartheid regime in South Africa. Students set up campus-based shantytowns or makeshift “shacks” that symbolically represented the “living conditions of many black South Africans.”[xvii] The protests pressured universities to relinquish their business ties to corporations that had financial investments in South Africa. Some divestment initiatives were coordinated by multiracial coalitions, while others were predominantly black. For example, the Progressive Black Student Alliance organized against South African apartheid and other foreign policies such as the U.S. interventions in Grenada and Nicaragua.

Other young activists of the post-civil rights cut their teeth in local organizing initiatives in cities such as the New Haven, Connecticut in the mid-late 1980s. The youth movement, or “Kiddie Korner” as it was called, was fostered by a coalition involving the Greater New Haven NAACP Youth Council, the African American Youth Congress (initially called the Black Youth Political Coalition), Elm City Nation, Dixwell Community House, and the Alliance of African Men. The coalition organized anti-gang violence initiatives, electoral organizing campaigns that eventually elected the city’s first black mayor, and mobilized youth around equitable education policies.

One important organization that emerged in the post-civil rights era was the Black Student Leadership Network (BSLN). The formation of the BSLN began in 1990 when Lisa Y. Sullivan, a community and political activist in New Haven, urged prominent civil rights activists such as Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF), to assist black student and youth activists in the development of a mass-based, black student and youth activist organization. In 1991, Sullivan and others organized a black student leadership summit at Howard University that recruited student and youth activists from around the country. After much deliberation, the summit attendees officially founded the BSLN. The BSLN’s parent organization was the Black Community Crusade for Children (BCCC), which operated as an arm of the CDF. For the next six years until its collapse in 1996, the BSLN linked a national advocacy campaign with local political and community initiatives in an effort to combat child poverty, political apathy, and public health epidemics.

Through its Ella Baker Child Policy Training Institute and Advanced Service and Advocacy Workshops, the BSLN trained over 600 hundred black students and youth in direct action organizing, voter education, child advocacy, and teaching methodology. The organization developed freedom schools in dozens of urban and rural cities and teamed with child advocacy groups to spearhead anti-childhood hunger initiatives. Beginning on April 4, 1994, the BSLN and local community activists launched its National Day of Action Against Violence (NDAAV) in concurrence with the observance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. The NDAAV activities, occurring in forty cities in 1994 and dozens more in 1995 and 1996, highlighted community-based strategies for reducing gun violence and police misconduct.

Among the more interesting set of youth and intergenerational initiatives emerging in the late 1990s and early 2000s was the Juvenile Justice Reform Movement (JJRM). JJRM campaigns in Louisiana, Maryland, California, and New York set out to reverse the zero-tolerance measures, shut down youth prisons that were known for human rights abuses, and end the disproportionate confinement of black and Latino youth in the juvenile justice system. These initiatives were coordinated by youth and adult-led advocacy organizations such as Project South, Youth Force of the South Bronx, New York’s Justice 4 Youth Coalition and Prison Moratorium Project, Baltimore’s Reclaiming Our Children and Community Projects, Inc. organization, Correctional Association of New York, Critical Resistance, the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, and the Maryland Juvenile Justice Coalition.

Similar to the BSLN, JJRM activists made an extensive effort to develop community-based responses to youth violence and crime. They developed what scholar-activist Sean Ginwright calls a “radical healing” approach that integrates community organizing, self-development, and consciousness-raising activities into a holistic approach to social justice.[xviii] In most cities where youth spearheaded campaigns to challenge mass incarcerations, the same youth groups were also at the forefront of rites of passage and violence reduction programs.

Moreover, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) made a concerted attempt to mobilize young people, especially black students, from 1989-2005. It created Union Summer in 1996 that placed young people as frontline organizers for locally based campaigns, including nearly a thousand interns in its first year. Modeled after SNCC’s Freedom Summer of 1964, the Union Summer field staff intentionally recruited black students through its HBCU plan that was first established a decade earlier as part of the AFL-CIO’s Organizing Institute. Blacks made up the majority of non-whites during the program’s latter years and students/youth of color (blacks, Latinos, Asians) comprised the majority of Union Summer organizers.

Black Youth in the Age of Black Lives Matter

The most recent wave of black youth and young adult activism has focused attention on criminal and juvenile justice reform. In 2007, young activists joined prominent civil rights leaders in mobilizing support for six black youth in Jena, Louisiana who were incarcerated as a result of a violent dispute between black and white teenagers. The black youth faced the prospect of a 100-year collective sentence, yet a similar punishment was not proposed for their white counterparts. As such, thousands of activists gathered in Jena on September 20, 2007 to protest the decision.

Six years after the Jena 6 case, young activists coalescing under the umbrella of the Movement for Black Lives Matter protested Stand Your Ground laws, as well as racialized and police violence targeting blacks. The movement started as the twitter hashtag, #BlackLivesMatter, by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi in response to the killing of Trayvon Martin and the Florida court’s exoneration of his killer, George Zimmerman. The movement blossomed after the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York as protests broke out across the country. Though young blacks made up a large number of the protesters, the movement has also galvanized non-black protestors.

The Movement for Black Lives Matter is composed of dozens of groups and activists. These include the official organization of Black Lives Matter and other well-known youth and young adult groups such as the Dream Defenders of Florida, Million Hoodies Movement for Justice in New York, Organization for Black Struggle in St. Louis, Gathering for Justice/Justice League NYC, and Black Youth Project 100 in Chicago. From July 24-26, 2015, these groups along with hundreds of young activists, convened in Cleveland, Ohio at the National Convening of the Movement for Black Lives.

The Movement for Black Lives Matter has attempted to reshape the dialogue around race, class, and the criminal justice system. It has further challenged the respectability narrative that deems the black poor and youth as pathological and denies them community recognition. This narrative reflects what political scientist Cathy Cohen calls the “secondary marginalization” of the black poor who are routinely the targets of social stigma by the black middle class.[xix] Accordingly, the Movement for Black Lives Matter situates marginal youth, including women and LGBT youth, at the forefront of social activism.

By all accounts, activists and groups at the forefront of the Movement for Black Lives Matter have a policy window or political opportunity to advance serious reforms of a broken criminal justice system. There is already evidence that the resistance has made a difference. State and local legislative bodies sponsored racial profiling measures in 2015. Congress approved the Death in Custody Reporting Act, and the U.S. Justice Department announced new rules to reduce racial profiling by federal law enforcement officials.

In August 2015, activists and researchers affiliated with the Movement for Black Lives Matter released a national platform called Campaign Zero that outlined ten policy recommendations for reforming police departments. These activists then garnered commitments from three presidential candidates in the Democratic Party (former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, and former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley) to develop comprehensive restorative justice measures if elected president.

Furthermore, the Movement for Black Lives Matter has fueled racial justice protests on college campuses. Taking a cue from the street protests of 2014, young activists from the University of Missouri at Columbia led a semester-long campaign in the fall 2015 protesting racial incidents at the college. After a hunger strike by a graduate student activist and a threatened boycott by the university’s football team, the University of Missouri president and chancellor resigned for not effectively responding to racial incidents on campus. Afterwards, a wave of college-based protests blossomed across the country.

Black Youth Activism: Lessons Learned From the 1930s to the 2000s

This overview of black youth activism from the 1930s to the 2000s underscores important lessons about how young people participate in grassroots mobilization initiatives, and the central role that black youth have in American politics. The first lesson is that movement bridge-builders or the leaders of movement infrastructures play an instrumental role in fueling black youth activism. They can generate opportunities for young activists to participate in movement campaigns through the use of creative organizing, or strategies that are intentionally designed to elevate the social and political status of black youth such that they become vehicles for popular mobilization.

As highlighted in Figure 1, movement bridge-builders use several strategies to position youth activists at the forefront social movements and politically salient initiatives. Some bridge-builders use framing to develop narratives that explain a particular problem that has relevance to marginalize groups. For the purposes of mobilizing youth, these narratives identify a problem, assign blame to it, and then propose solutions to resolving the problem.[xx] For example, the Black Lives Matter frame has been useful in fueling youth protests against racialized killings by law enforcement officials. It has even been an agenda-setting instrument in the 2016 presidential campaigns as Democratic Party candidates Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and Martin O’Malley aligned their criminal justice platforms with Black Lives Matter.

Movement bridge-builders will also intentionally position black youth at the forefront of a particular policy debate, as did Mary McLeod Bethune to pressure the federal government to adopt economic justice measures for African Americans during the Great Depression. This is accomplished by using a strategy called “positionality” that intentionally alerts grassroots organizations and allies about political decisions or regressive policies that affect young people. The objective is to dramatize the impact of these decisions and policies on young people and create opportunities for intergenerational collaborative initiatives. This then positions young activists as the group that is best positioned to resolve these challenges. For example, the local campaigns to reform juvenile justice systems used positionality to garner support for young activists among street workers, educators, child advocates and other activists who were unfamiliar with the dimensions of juvenile justice policies. These campaigns alerted local groups and leaders about abuses in youth prisons and the harmful impact of zero tolerance policies.

Movement bridge-builders will further link the interests and collective identities of local activists and adult-led groups – or what are referred to as indigenous networks – with the goals of young activists. The intent is to create opportunities for young people to unite their interests with indigenous networks, as well as activate or appropriate these networks such that they can support youth-based movements. As an example, the AFL-CIO leveraged (or appropriated) local labor unions in order to garner their support for the Union Summer program.

In general, the central role of movement bridge-builders is essential to understanding how youth-based movements are sustained. Bridge-builders sow the seeds of black youth activism by identifying strategies and tactics that allow youth to become vehicles for popular mobilization initiatives. They help youth acquire the resources to sustain activism and connect young activists to indigenous groups and seasoned activists. They also help to develop the leadership capacity of young people.

The significant role of movement infrastructures in cultivating black youth activism is another important lesson of this overview. These included youth-led organizations such as the Southern Negro Youth Congress, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Student Organization for Black Unity, and those affiliated with the Movement for Black Lives Matter. Others joined adult-led or network-affiliated youth organizations such as those that led the juvenile justice initiatives in the 1990s and 2000s as well as the Union Summer campaign. Still, some activists belonged to multi-generational/intergenerational infrastructures such as the Black Student Leadership Network.

Movement infrastructures (youth-led, multi-generational, network-affiliated) facilitate youth involvement in social justice initiatives. Youth-based initiatives require resources, linkages with indigenous organizations, and political education, all of which are coordinated by movement infrastructures. Movement infrastructures also establish norms and standards for democratic deliberation among young activists. Thus, movement infrastructures that are cohesive and democratic are more likely to minimize internal conflict and mediate philosophical divisions between competing activists.

The third lesson of this overview underscores how black youth are shaped by the political, social, and economic conditions of their respective time periods. The Great Depression of the 1930s politicized black youth during this period to embrace more militant economic justice initiatives and to support labor unions; Cold War politics impacted young activists in the 1950s and 1960s by allowing them to make a direct connection between the struggles for racial democracy in the United States and the promotion of democracy in the international arena; and the conservative movement’s resurgence between the 1960s and the 1980s heightened the racial or oppositional consciousness of young blacks during this period.

The social, political, and economic conditions are equally important for understanding youth activism in the age of the Black Lives Matter movement. Black youth and young adults in the twenty-first century have been the disproportionate targets of state violence, racial profiling practices such as the “Stop-and-Frisk” policing approach in New York City, and “Stand-Your-Ground” measures including Florida’s law that lead to the killing of Trayvon Martin. These policing practices have converged with a broader mandate by municipal officials to remake cities into attractive destinations for middle-class residents. Large cities are increasingly displacing blacks and gentrifying moderate-income residents. They are also downsizing public sector programs and institutions (housing, schools, jobs, utilities), which is adversely affecting poor blacks and black youth. Policing practices are thus reinforcing a displacement ethos that is increasingly carried at the expense of moderate-income and young blacks. These conditions have amplified the concerns of young activists affiliated with the Movement for Black Lives Matter.

Overall, black youth activism has been an important vehicle for addressing racial, economic and social injustices. Young activists have raised awareness about black poverty during the Great Depression and laid the groundwork for the repeal of state and local poll taxes in the 1940s. Black youth participation in marches, sit-ins, freedom rides, and local organizing initiatives from the 1950s-1970s challenged racial terrorism in the South. Black youth-based formations are also credited with the passage of seminal civil rights laws in the 1960s including the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. By the 1980s, blacks and multi-racial networks organized protests at 100 universities in order to end racial apartheid in South Africa. A decade later, the Black Student Leadership Network and the AFL-CIO’s Union Summer program set up dozens of freedom schools, organized labor initiatives, and called the nation’s attention to systemic poverty. The Movement for Black Lives Matter has also been instrumental in advancing anti-racial profiling platforms and addressing state violence against blacks.

In addition, academicians (social scientists and education specialists) have an important role to play in supporting black youth activism. If youth-based movements are going to be viable responses to inequality in the twenty-first century, then black social scientists must be integral to this struggle. There are multiple roles that they can play including assisting young activists with press releases, op-eds, strategies, fundraising initiatives and research.

During the protest waves of the 1930s-1940s and the 1950s-1970s, there was a partnership between resistance movements and hybrid academicians (or scholars who had one foot in movements and the other one in the academy). Ira De Reid, E. Franklin Frazier, and Charles Johnson belonged to a cadre of black scholars commissioned by the American Council on Education in the 1940s to study the challenges facing black youth. Their pioneering studies provided a broader context for shaping radical youth organizations such as the Southern Negro Youth Congress.

The National Conference of Black Political Scientists was also established in 1969 as an outgrowth of the civil rights and black power movements. More recently, black political scientists have been on the frontlines of the Movement for Black Lives Matter. Political scientist Cathy Cohen at the University of Chicago assisted youth with the formation of the Black Youth Project 100, one of the leading organizations in the movement. As the co-founder of the Black Lives Matter affiliate in Los Angeles, Professor Melina Abdullah has organized protests against the Los Angeles Police Department, which has one of the highest rates of killing unarmed blacks in the nation.

[i]. I use the terms African American and black interchangeably.

[ii]. Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1999), 229-230.

[iii]. E. Franklin Frazier, Negro Youth at the Crossways: Their Personality Development in the Middle States (New York, New York: Schocken Books, 1940); Charles S. Johnson, Growing Up in the Black Belt: Negro Youth in the Rural South (New York, New York: Schocken Books, 1941); Jesse Atwood, Thus Be Their Destiny: The Personality Development of Negro Youth in Their Communities (Washington, DC: American Council on Education, 1941); Ira De Reid, In a Minor Key: Negro Youth In Story and Fact (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1971 [1940]); Allison Davis and John Dollard, Children of Bondage: The Personality Development of Negro Youth in the Urban South (Washington, DC: American Council on Education, 1946).

[iv] Raymond Wolters, The New Negro On Campus: Black College Rebellions of the 1920s (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975); St. Claire Drake, Interview by Robert E. Martin, June 19, 1968, 46-47, Ralph J. Bunche Oral History Collection, Civil Rights Documentation Project, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Washington, D.C., 1969.

[v] George Schuyler became one of the leading black conservatives in the country by the 1950s. Yet, he was a prominent activist and cultural critic allied with civil rights organizations in the 1920s-1940s.

[vi] Thomas Bynum, NAACP Youth and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1936–1965 (University of Tennessee Press, 2013), pp. 6-7.

[vii]. Ibid., 59-74.

[viii]. Sekou M. Franklin, After the Rebellion: Black Youth, Social Movement Activism, and the Post-Civil Rights Generation (New York: NYU Press, 2014), 59.

[ix]. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Southern Negro Youth Congress, #100-HQ-6548, Part I, “Undeveloped Leads,” 28-30.

[x]. Johnetta Richards, “The Southern Negro Youth Congress: A History,” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 1987, 48.

[xi] Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2011).

[xii] Ella Baker, Interview by John Britton, June 19, 1968, Ralph J. Bunche Oral History Collection, Civil Rights Documentation Project, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Washington, D.C.

[xiii]. Robert P. Moses and Charlie Cobb, Jr., “Organizing Algebra: The Need to Voice a Demand,” Social Policy 31, no. 4 (Summer 2001): 8.

[xiv]. Robert C. Smith, We Have No Leaders: African Americans in the Post-Civil Rights Era (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996).

[xv]. See Clarence Lang, “Political/Economic Restructuring and the Tasks of Radical Black Youth,” The Black Scholar vol. 28, no. 3/4 (Fall/Winter 1998): 32-33; Also see Luke Tripp, “The Political Views of Black Students During the Reagan Era,” The Black Scholar vol. 22, no. 3 (Summer 1992): 45-51.

[xvi]. Becky Pettit and Bruce Western, “Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration,” American Sociological Review 24 (2009): 156-165.

[xvii]. Sarah A. Soule, “The Student Divestment Movement in the United States and Tactical Diffusion: The Shantytown Protest,” Social Forces vol. 75, no. 3 (March 1997): 857-858.

[xviii] Sean Ginwright, Black Youth Rising: Activism and Radical Healing in Urban America (New York: Teachers College Press, 2009).

[xix]. Cathy Cohen, Democracy Remixed: Black Youth and the Future of American Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 28.

[xx]. David A. Snow and Robert D. Benford, “Master Frames and Cycles of Protest,” in Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, ed. Aldon Morris and C. McClurg Mueller (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 137.

*This lesson plan was originally published in the Association for the Study of African American Life & History’s Black History Bulletin and is reprinted here by permission of the author and is available here.

Trump Syllabus K12: Lesson Plans for Teaching During this New Age of Resistance (#TrumpSyllabusK12)

created & compiled by Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

with Alicia Moore, Ph.D. & Regina Lewis, Ph.D.

Lesson Plans for Teaching During this New Age of Resistance (#TrumpSyllabusK12)

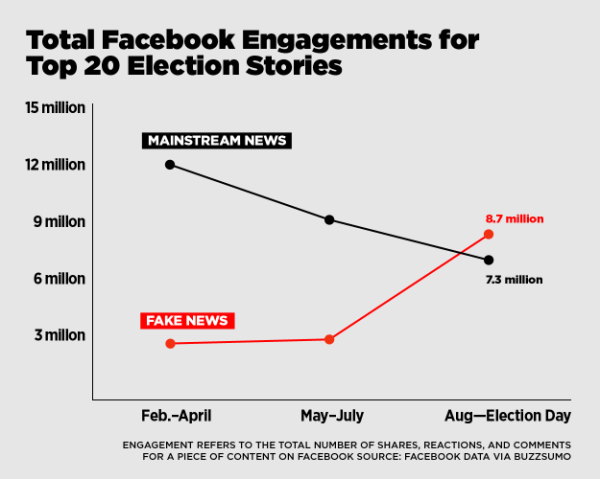

#TrumpSyllabusK12 is a compilation of lesson plans and resources written by and for K-12th grade teachers (and college educators) for teaching about the 2016 presidential campaign; about resistance and revolution; about white privilege and white supremacy; about state-sanctioned violence and sanctuary classrooms; about fake news and Facebook; and, about freedom and justice. It is designed to transform our classrooms into liberated nonsexist nonmisogynistic anti-racist anti-classist spaces without any boundaries or borders. It is meant to liberate and free our students by providing them with lesson plans to challenge them to become global critical thinkers. We invite you to join with us as we actively work to push back against the establishment of this New World Order and we draw our line in the sand and work to liberate and change the world, one student at a time.

The syllabus is divided into four sections: the opening section provides resources and tools to ground the classroom discussion; Section One: Examining Campaign 2016, includes lesson plans and resources that examine the presidential campaign of Donald J. Trump and Hillary Rodham Clinton (see Clinton Syllabus 1.0 for more information); Section Two: Politics in the “Post-Trump” Narrative, which includes lesson plans and resources that explore the ways that we can transform our classes into safe liberated spaces designed to openly discuss and address white privilege, race, and citizenship; and, Section Three: From Dr. King to President Trump: Examining History, Now & Then, which consists of lesson plans and resources provided by the National Visionary Leadership Project that explore and connect the work from the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter to the current activist work against the Trump Administration.

Each lesson plan is presented in its entirety and includes Warm Up and Group Activities, Essential Questions and Objectives, Resources, an Essay or an Overview, and they connect directly to the Common Core Standards for Math, History, or Language Arts; and, to the National Council of Social Studies Standards.

Please note that lesson plans are still being accepted at griotonthego@gmail.com and are being added daily.

(ES=Elementary School; MS=Middle School; HS=High School)

######

TABLE OF CONTENTS

RESOURCES & TOOLS TO GROUND THE DISCUSSION

1. America is a Divided Nation: Singing the Post-Trump Blues **NEW**

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

2. Teaching After the Election of Trump **NEW**

-The Zinn Education Project

3. Opinion Editorial: “These Are Our First 100 Days, Too” **NEW**

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

4. Resistance 101: A Lesson for Inauguration Day Teach-Ins and Beyond **NEW**

-Teaching for Change

5. 40 Acres, A Mule, & $50 Dollars: Making the Case for Reparations **NEW**

-Conra Gist, Ph.D., and Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

6. Tips for Facilitating Classroom Discussions on Sensitive Topics

-Alicia Moore, Ph.D., and Molly Deshaies

SECTION ONE: EXAMINING CAMPAIGN 2016

7. The Electoral College vs The Popular Vote: Who Should Choose OUR President? (HS)

-Jocelyn Thomas

8. Exploring the (New) Political Climate (MS)

-Nadiera Young

9. Exploring the Reasons Why Trump Won (MS/HS)

-Gloria Ladson-Billings, Ph.D.

10. Exploring the Fake News Cycle (MS)

-Baba Ayinde Olumiji

11. Using Photographs to Explore Differing Political Perspectives (ES)

-Alicia Moore, Ph.D., and Angela Davis Johnson

12. Trump and Gender Bias, By the Numbers (HS)

-Kelly Cross Ph.D.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES (POETRY):

13. Oya for President (to be read OutLoud)

-Alexis Pauline Gumbs

14. Mourning in America: A Black Woman’s Blues Song

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

15. Songs in a Key Called Baltimore

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

SECTION TWO: POLITICS IN THE “POST-TRUMP” NARRATIVE

16. Harassment and Intimidation in the Aftermath of the Trump Election: What Do We Do Now? (MS/HS)

-Sarah Militz-Frielink and Isabel Nunez, Ph.D.

17. From “I Have A Dream” to “I Dream of a World”: Steps to Creating a Sanctuary Classroom (All Grades)

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D.

18. Hope, Action, & Freedom in the Times of Uncertainty (HS)

-Conra D. Gist,Ph.D., Angela Davis Johnson, & Tyson E.J. Marsh, Ph.D.

19. Writing White Privilege, Race, and Citizenship: Reading Angela Davis, Toni Morrison, Claudia Rankine, and Walt Whitman (HS)

-Ileana Jiménez

20. A Pedagogy of Resistance in the Struggle Against White Supremacist State-Sanctioned Violence* (MS/HS)

-Tyson E.J. Marsh, Ph.D.

21. Lessons in Black Feminist Criminology: Disrupting State and Sexualized Violence Against Women and Girls #GrabtheEmpowerment (HS)

-Nishaun T. Battle, Ph.D.

22. Giving Voice & Making Space: Dismantling the Education Industrial Complex in an Effort to Free Our Black Girls* (MS/HS)

-Aja Reynolds & Stephanie Hicks

23. Exploring the “Crisis” in Black Education from a Post-White Orientation* (MS/HS)

-Marcus Croom

24. The African American Saga: From Enslavement to Life in a Color-Blind Society (Or Racism Without Race)*(HS)

-Yolanda Abel, Ed.D., and LeRoy Johnson

25. #Evolution or Revolution: Exploring Social Media through Revelations of Familiarity* (HS)

-Kimberly Edwards-Underwood, Ph.D.

26. Replace Fear with Curiosity: Using Photographs and Poetry to Process Election 2016 (ES)

-Tracy Kent-Gload

27. #WeGotNext: Black Youth Activism and the Rise of #BlackLivesMatter* (HS/MS) **NEW**

-Sekou Franklin

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

28. Steps to Combating Anti-Muslim Bullying in Schools

-Mariam Durani, Ph.D.

29. #ClintonSyllabus 1.0

-Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D., Alicia Moore, Ph.D., Regina Lewis, Ph.D.

30. Book: Black Lives Matter (Special Reports)

–

31. Book: Shock Exchange: How Inner-City Kids from Brooklyn Predicted the Great Recession and the Pain Ahead **NEW**

–

*The marked lesson plans above were originally published in the Association for the Study of African American Life & History’s Black History Bulletin and are reprinted here by permission of the authors.

SECTION THREE: FROM DR. KING TO PRESIDENT TRUMP: EXAMINING HISTORY, NOW & THEN

The following lesson plans and historiographies were originally published on the National Visionary Leadership Project’s website. They were written by Karsonya Wise Whitehead and are reprinted here with her permission.

32. From Plessy to Brown: Examining the Ways We Worked to Overcome (ES/MS)

33. Examining the Modern Civil Rights Movement & the Birth of Our Activist Spirit (MS/HS)

34. From Brown (v Board) to Black (Power): Examining the Roots of the Civil Rights Movement **NEW**

35. Nevertheless They Persisted: Black Women & The Fire Within Them (Essay) **NEW**

36. Nevertheless They Persisted: Black Women & The Fire Within Them (Lesson Plan) (MS/HS) **NEW**

Exploring the “Crisis” in Black Education from a Post-White Orientation*

Marcus Croom

Intended Audience: Middle School And/Or High School

Overview: Children are socialized into the thought and practice of race as common sense by the time they enter Kindergarten (Apfelbaum, Norton, & Sommers, 2012). By middle school and high school, children have had very sophisticated experiences with race, but typically have not been adequately supported as they navigate both normative human development and race production in their lives. This double task can be especially challenging for children raced as Black in American society and in American schooling (Murrell, 2009). Our aim is simply to begin, with middle and high school students and teachers, by defining what race is and then offering students and teachers an opportunity to (re)define themselves in light of their own better understanding of race. Teachers will prepare to facilitate this beginning by first engaging in this activity and assessing their own work.

National Council for Social Studies (NCSS) Standards:

Teachers are charged with providing opportunities that will:

History

- enable learners to develop historical understanding through the avenues of social, political, economic, and cultural history and the history of science and technology.

Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

- help learners analyze group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture in both historical and contemporary settings;

- assist learners in identifying and analyzing examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and efforts used to promote social conformity by groups and institutions;

- enable learners to describe and examine belief systems basic to specific traditions and laws in contemporary and historical movements;

- assist learners as they explain and apply ideas and modes of inquiry drawn from behavioral science and social theory in the examination of persistent social issues and problems.

Culture and Cultural Diversity

- assist learners to apply an understanding of culture as an integrated whole that explains the functions and interactions of language, literature, the arts, traditions, beliefs and values, and behavior patterns;

- have learners interpret patterns of behavior reflecting values and attitudes that contribute or pose obstacles to cross-cultural understanding.

Goals of Lesson Plan

Teachers and students will understand race as a consequential social practice, how it contrasts with a common sense understanding of race, and use dialogues and writing to (re)define themselves in light of a richer understanding of race.

Lesson Plan

Objectives

- Teachers and students will create a safe setting for demystifying race as a human cultural practice.

- Teachers and students will read and discuss the definition of race provided (Race is a consequential social practice).

- Teachers and students will read, discuss, and debate a point of view about an article.

- Students will free-write a shared or unshared Race Reflection.

Warm up (5-10 min)

Teacher will pose this question and discuss:

“Who are your people and what makes each of you members of the same group?”

Although directed to the whole class, this question is really an individual query. The whole class is not assumed to be members of the same group. Individual students should have an opportunity to respond to and dialogue about the question. Teacher should engage in the discussion, revealing their own personal view, but silently note instances when students (or when teachers themselves) offer common sense notions of race to identify themselves or the group with which they identify.

Activity (Instruction Input) (25-30 min)

Teacher will post a T-chart to facilitate a whole class comparison of the common sense perspective of race and the consequentially social practice perspective of race. Define the “Race is Common Sense View” as the perspective wherein race is a human feature that is self-evident and identifiable. Define the “Race is Consequential Social Practice View” as the perspective wherein humans create and consume race for human ends. Students will provide examples of how race is commonly understood as “self-evident and identifiable” on the left side of the T-chart (e.g. skin, bone, blood, hair, name, language, culture, etc.). On the right side of the T-chart, students will provide examples of how humans “create and consume” race (labeling, ranking, storying, symbolizing, social-classing, boundary-making, etc.).

Teacher will launch instruction by saying (something like):

“Today, we are going to distinguish between two ways of understanding race. The first way is nothing new. In fact, we’ll call it the common sense view of race. The second way is one you’ll quickly catch on to. We do it all the time, but you probably haven’t thought about race this way; we’ll call the second way the social practice view of race.”

Applying the article below to instruction, the teacher will discuss and complete the T-chart as described above.

- Once the T-chart is completed, the teacher will provide students with a copy of the article about Rachel Dolezal. Choose Option 1 or Option 2 to complete the reading of the article.

Option 1: Students will form groups of three or four and “jigsaw” read the entire article:

- Each member will select a portion to read and report back to the entire group.

Option 2: Teacher will select an excerpt from the article, student groups will read excerpt, and discuss excerpt (e.g., From: “Rachel and her college friends describe Belhaven as predominantly white.” To: “Finally, she says, she could live an authentic life.”).

- Student groups will prepare to orally argue whether the “Common Sense View” or the “Consequential Social Practice View” of race best explains the racial identity of Rachel Dolezal.

- Students will respond to the following: “Does Rachel Dolezal have racial identity? If so, which one(s) and why (i.e. according to “Common Sense” or “Consequential Social Practice”)? If not, why not (i.e. according to “Common Sense” or “Consequential Social Practice”)?”

- Teacher will engage with the arguments offered by each group without suggesting which argument is “right or wrong.” The point is for the teacher to invite a well-reasoned oral argument from all groups (teachers may provide and model a common oral argument structure to support the development of a well-reasoned oral argument; this kind of model may also be provided and modeled in the following written assessment).

Assessment (15-20 min)

Students will free write a Race Reflection using the following prompt:

“Do you have racial identity? If so, who are your racial people and what makes each of you members of the same group? If not, why not?”

- Teachers may invite a few willing students to share their Racial Reflection with the whole class, if teachers feel comfortable with managing, with credibility and sensitivity, the possibility of unexpected or unpopular viewpoints.

- Teachers will collect and review each Race Reflection to determine if the student has a well-reasoned reflection. Race Reflections that derogate self or others should be appropriately discussed with the individual student. Because this is a free write, teachers will not assess student writing for use of conventions.

- Beyond sound reasoning, teachers are looking for evidence that students understand the difference between the “Common Sense View” and the “Consequential Social Practice View” of race. Students are not required to adopt one view of race or the other; they may be inconclusive. Again, this entire lesson is only a beginning effort to develop a richer understanding of race as a human cultural practice.

This writing assignment can be extended by providing a model publishable text, offering opportunities for student-lead research, and offering teacher-lead writing support to students (across multiple drafts) that results in a publishable text, including appropriate use of conventions.

Background Information

Reading “The Crisis in Black Education” from a Post-White Orientation

As a literacy scholar, I have spent a great deal of time theorizing race in pursuit of practical ends–advancing the literacy practices of Black children in U.S. schools. This themed volume focused on the “Crisis in Black Education” caused me to reflect on this question: What makes “Black Education,” Black? Black as a category of race needs to be explained rather than assumed. In this essay, I will argue that race can be theorized either as common sense or as consequential social practice. I will also offer contrasting views of what “crisis” may mean according to each theory. I conclude by suggesting that this moment of “crisis” is thrusting upon us an opportunity to read the word and the world from a post-White orientation. By post-White orientation, I mean a racial understanding and practice characterized by a) unequivocal regard for “non-White” humanity, especially “Black” humanity; b) demotion of “White” standing (i.e., position, status); c) rejection of post-racial notions; d) non-hierarchical racialization; and e) anticipation of a post-White sociopolitical norm. Figure 1 is an illustration depicting post-White orientation as it differs from White superordinate racialization on one hand and postracialism on the other.

Figure 1

Racing on a Different Track

According to O’Connor, Lewis, and Mueller (2007), race is “undertheorized in research on the educational experiences and outcomes of Blacks” (p. 541). They find that race has been understood through two dominant perspectives: race as variable and race as culture. These understandings of race ignore or minimize heterogeneity, intersectionality, and the institutional production of race and racial discrimination where Black persons are concerned. Alternatively, O’Connor et al. (2007) argue that race is produced as a social category and urge that future research take an orientation of race aligned with the following:

(a) theoretical attention to how race-related resources shape educational outcomes, (b) attention to the way race is a product of educational settings as much as it is something that students bring with them, (c) a focus on how everyday interactions and practices in schools affect educational outcomes, and (d) examination of how students make sense of their racialized social locations in light of their schooling experiences. (p. 546)

Such studies will continue to uncover how schools produce race as a social category. Research focused on race production, then, will have implications for talking and writing about race and how race impacts views on education. The following framework conceptualizes race as common sense and race as consequential social practice[1].

Race as Common Sense: The Wrong Train

Sociologist Celine-Marie Pascale (2008) finds that race is widely understood as “common sense,” which she defines as “a saturation of cultural knowledge that we cannot fail to recognize and which, through its very obviousness, passes without notice” (p. 725). In other words, these are

assumptions that we make about life and the things we accept as natural. Common sense leads people to believe that we simply see what is there to be seen. For example, common sense leads us to believe that we simply ‘see’ different races. (p. 725)

She concluded that common sense knowledge of race was discussed in four ways: “as a matter of color, nationality, culture, or blood” (p. 726). What all of these ways have in common is that race is understood uncritically; that is, in a manner that does not question serious incoherencies and contradictions. A deeper, more important point about race as common sense is how it assumes White superiority (Mills, 1997; Puzzo, 1964). The racially White superordinate assumption included in common sense notions of race is morally bankrupt and indefensible.

Race as Consequential Social Practice: All Aboard!

Race as consequential social practice is defined as the individual, collective, institutional, or global production of race, through meaningful ways of being, languaging, and symbolizing, and the effects of such race production (big “D” Discourse and little “d” discourse; see Gee, 1990). I trace the beginning of this understanding of race to W. E. B. Du Bois’ book, The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois’ “study of black identity marks a turning point away from biology and towards discursive interaction” (Wilson, 1999, p. 194). As such, Du Bois must be counted among foundational theorists when we historicize the understanding that race is a D/discursive, socially constructed, consequential human practice.

The antecedents/roots of defining race as consequential social practice can be found in the vindicationist tradition, a tradition coined by W.E.B. Du Bois according to anthropologist Kevin Michael Foster. Foster (1997) explains further,

According to Drake, vindicationism reflects the work of scholars to ‘set straight the oft-distorted record of the Black experience and to fill in the lacunae resulting from the conscious or unconscious omission of significant facts about Black people’ (Drake 1987, vol. 1: xviii). Today, even where vindicationism is not the explicit goal of Black scholars, the influence of this tradition is often apparent. Vindicationism may not be the defining characteristic for the work of African-descended scholars, but it is a recurrent feature (Baker 1994, Franklin 1989). (p. 2)

The vindicationist tradition advances and sustains us as persons raced as Black. As such, the vindicationist tradition and Du Bois’ work are critically important today as they were at their origins because “race emerged in language, and it survives in language” (Happe, 2013, p. 135). Further, race is also produced in ways that have grave consequences for human beings. For example, Happe (2013) uncovers that genes are made into artifacts of race and, in fact, do not corroborate race as the biological, common sense view of race alleges. Race, then, should be interrogated and denaturalized as a self-evident feature of the human body, even at the subcellular level, in contradiction to those who, whether unlettered or lettered, promote genes, skin, or other claims about the human body as corroboration of race as common sense (Herrnstein & Murray, 1996, p. 563). Again, race is consequential social practice. Whenever race occurs, it does not occur naturally; rather, race occurs because humans create and consume race for human ends. Each of these ways of understanding race–as common sense or as consequential social practice–may influence how race and “Black education” are viewed.

Race and “Black Education”

When we understand race as common sense, “Black education” may mean the realm of education that is a subset of, or is even apart from, “White education.” Said another way, “Black education” is education from Black people’s perspective, on Black people’s terms, and in Black people’s experience. From this orientation, “Black education” is a self-explanatory label that marks the largely homogenous “Black” experience of education in the U.S. according to those who are themselves actually “Black.”

The “crisis” in “Black education,” when race is understood as common sense, is a crisis in at least two ways. First, Black education is assumed to be subordinate to White education. Second, Black education primarily or exclusively involves Black persons and places—Black persons and places assumed to be subordinate to White persons and places. Accordingly, the question becomes what can be done about those inferior “Black children” and their inferior “Black education”? To be clear, this is not my own view; rather I am articulating the common sense view of race where education and crisis are concerned. As such, within the “Black” boundary there is catastrophe, and beyond the “Black” boundary, all is well or is at least better.

When we understand race as consequential social practice, “Black education” may mean the social partitioning of access to some aspect(s) of accumulated human knowledge, according to the racial hierarchy of “White” over “Black.” In other words, education itself is not racialized unless persons socially produce education as such through, for example, talk, text, or some other practice. Importantly, I hasten to add, education can be racialized for both ethical and unethical reasons. I cannot overstress this point. A “crisis” in “Black education,” when race is understood as consequential social practice, is a crisis in terms of thought, practice, systems, and institutions, whether local or global. As such, the question becomes what patterns and barriers are hostile to the humanity of persons raced as “Black”? I believe that this question begins to approach the essence of the vindicationist tradition (Drake, 1987) that Carter G. Woodson (1933) lived, worked, and struggled according to, along with many others like Du Bois. From the consequential social practice understanding of race, we who are raced as “Black” are always already fully human, and thus legitimate inheritors of all accumulated human knowledge, but our legitimacy as inheritors of all human knowledge and our intersectional, heterogeneous humanity are not always adequately honored and regarded. Such dishonor and disregard toward our human inheritance and plentitude is evidenced by historic and current thought and practice, including the processes of education (whether in school or out-of-school).

With this second perspective of “Black Education crisis” in mind, it becomes obvious why, yet again, we are faced with the need to exclaim, “Black lives matter.” It should comes as no surprise that the organization of schools and classrooms, the instructional practices therein, and the resources and materials apportioned to places raced as “Black” would produce pipelines to prison and poverty (Ladson-Billings, 2006). Given the innumerable artifacts, institutions, and ideologies derived from Western Europeans’ invention of race, we who are raced as “Black” fully expect to fight philosophically, epistemologically, theologically, theoretically, hermeneutically, linguistically, and with our own colored, clenched hands to protect our humanity, the humanity of our children, our loved ones, and our communities. For many persons raced as “Black” in the U.S., this is the American way.

Our present times have shown us again that we have a choice to make: will we choose to orient ourselves to race as common sense, reading the word and the world only according to Western European design? Or, will we choose the post-White orientation, wherein we are critically aware of the consequential social practice that metaphorically, and quite literally, writes the codes of the racialized matrix in which we live?

I have not argued that there is no such thing as race or racism. Neither have I argued that people who are raced as Black, should not call themselves “Black.” Further, I reject post-racialism in all its forms. I have argued that race and racism are produced by human thought and practice for human ends. Most of these human ends for race production are patently White superordinate (obviously including racism), but thankfully some human ends for race production are post-White oriented and human nurturing for persons categorized as “Black” (i.e., vindicationist). The issue is not the label “Black” per se, the issue is whether one is “Black” on racially subordinate terms or on human-peer terms (Woodson, 1933, pp. 199-202). As this suggests, post-racialism fails to hit the point. The point is race production and whether the race production in question is ethical or unethical. Rather than post-racialism, we should pursue the development of racial literacies–the acquired, critical, cultural toolkit that supports human well-being amid the social thought and practice of race (http://racialliteracies.org).

Whatever the current raced as Black education crisis may be, we should face it on human terms, rather than on normatively White superordinate terms. Perhaps the “Crisis in Black Education” is the recurring, practical repercussions of not yet realizing, together, what it means for persons, raced as Black, to be human (Wynter, 2006).

Teacher Resources

- The Mis-Education of the Negro by Carter G. Woodson (1933); especially chapter four “Education Under Outside Control.”

- Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real about Race in School edited by Mica Pollock (2008); especially section A “Race Categories: We Are All the Same, But Our Lives Are Different” and section B “How Opportunities Are Provided and Denied Inside Schools.”

- “In Rachel Dolezal’s Skin” by Mitchell Sunderland (2015).

- Tips for Facilitating Classroom Discussions on Sensitive Topics. by Alicia Moore, Ph.D., and Molly Deshaies.

- Developing a Positive White Identity by Racial Equity Tools.

- “The Crisis in Black Education” Executive Summary. Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Notes

[1] In previous work, instead of “social practice” I used the big “D” and little “d” distinction offered by Gee (1990) to refer to “Discourses” as meaningful ways of being in the world and “discourses” as meaningful ways of using language or symbols in the world. For example, talk or texts are “discourses” employed in the “Discourses” of race, Black, White, Latino, Asian, Native American, etc. Both “D/discourse” and “social practice” are intended to convey the same meaning within the practice of race theory (PRT).

*This lesson plan was originally published in the Association for the Study of African American Life & History’s Black History Bulletin, v79, (2) and is reprinted here by permission of the author.

Jocelyn Thomas

Intended Audience: High School Students

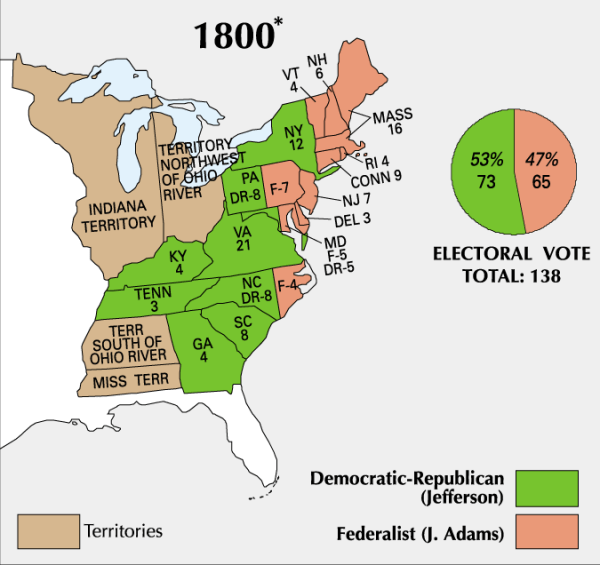

Objectives: Students will be able to define the electoral college; describe how the Electoral College works; explain the impact that the Electoral College has had on major political issues (i.e., slavery); discuss the current concerns about the Electoral College system in regards to Election 2016; and, argue whether the Electoral College is an effective and/or necessary part of electing a president.

Overview: “The founding fathers established The Electoral College in the Constitution as a compromise between election of the President by a vote in Congress and election of the President by a popular vote of qualified citizens.” [i] “While the election of the president and vice-president was provided for in Article II, Section 1, Clauses 2, 3, and 4 of the U.S. Constitution, the process today has moved substantially away from the framers’ original intent. Over the years, a combination of several factors has influenced the Electoral College and the electoral process.”[ii] Nevertheless, even after all of these years, as subsequent tweaks to the process, the process has been determined to be confusing, with many intricacies that make it difficult for most Americans to understand. This lesson will give students the opportunity to understand these intricacies while thinking critically about the merit, or lack thereof, of this historically, and sometimes, indecisive[iii] process.

Scope and Sequence: This lesson asks students to explore what the framers of the United States Constitution considered to be the best way to elect the president and vice-president of the United States – the Electoral College. As well, the lesson provides opportunities for students to analyze, synthesize, evaluate, and discuss the election of the president through the electoral college versus the popular vote and assess the impact of the Electoral College process.

Lesson Plan

Part 1: Who determines who becomes the President of the United States?

Hook: The electoral college is something that we hear a lot about these days. Some people believe that the electoral college is a broken system.

Key Vocabulary

- Popular Vote—results of a presidential election based on how individual citizens vote.

- Electoral College Vote—results of presidential election based on how representative electors vote.

- Popular Sovereignty—the idea that the government (at all levels) is controlled, ultimately, by the will of the people

[i] What is the Electoral College? https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/electoral-college/about.html

[ii] National Archives: Tally of the 1824 Electoral College Vote. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/electoral-tally

[iii] Electoral College & Indecisive Elections. http://history.house.gov/Institution/Origins-Development/Electoral-College/

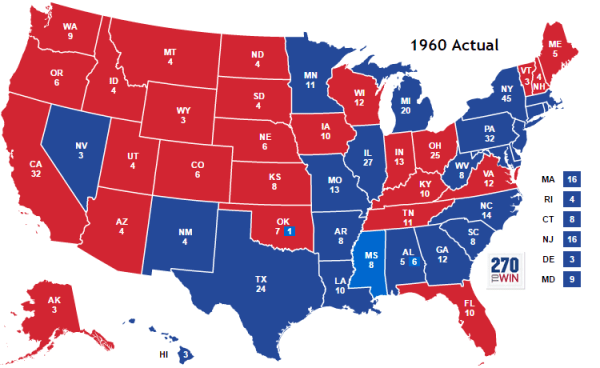

Analysis Questions: 1960 Presidential Election Interactive Map

- What are your first impressions of this map?

- How many electors voted in the election of 1960?

- How many were needed to win?

- How did your home state vote?

- What does it tell you about the election of 1960?

The Constitution: Article II

Section 1. The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:

- Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

- The Congress may determine the Time of choosing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

Analysis Questions: The Constitution: Article II

- How long is the presidential term?

- How do we determine the number of electors each state has?

- What is the job of the electors?

- How do electors vote?

Stop and Talk

- According to this system, who determines who is President of the United States?

- Do you think that system is fair? Why or why not?