Musings…Thoughts On Cultivating My Green Thumb While Raising My Boys

©2013 by Karsonya Wise Whitehead

September 2: I woke up this morning thinking about war and how senseless it is to “fight” for peace and use violence as a way to get to a state of nonviolence. I thought about the only two wars that I believed were completely justified: the Revolutionary War, where we as a nation fought for our independence from British rule; and the Civil War, where the Union fought for the end of American enslavement. Both of these were life and death situations that happened in our country (on our soil) and where violence was the only way that the other side would retreat and that true change would come. I am concerned that our dear sweet President is dragging us into another volatile situation that might take us years to get out of (remember the ten-year hunt for Osama bin Laden). I am alarmed by how casually he talks of going to war as if hundreds (or maybe thousands) of innocent men, women, and children will not be impacted when bombs from planes that are driven by men and women who are miles away from the center of death and destruction.

I feel as if the world is falling down around me and that I am not doing enough to keep it upright. I woke up this morning and I looked at my hands because in my dreams I had blood on them that I could not wash off, no matter how hard I tried. I realized after I settled back down on my bed that when my President chooses to go to war and my elected officials support him, and my fellow citizens execute his orders, then my hands like theirs are bloody. I am just as responsible. When I do not speak up and speak out then I am teaching my children to act as sheep, blindly following wherever their leaders will take them. I think of leaders like Hitler, Jim Jones, Robert Mugabe, Kim Jong-II, and Idi Amin Dada, men who abused their power and are directly responsible for the deaths of thousands of people. I must be the change, I must be the change, I must be the change that I want to see in the world and I must model the type of change that I want my sons to embrace and one day become.

September 1: Dear Mr. President: now that you have drawn a line in the sand and have decided that America is once again called upon to be the peacekeepers for the entire world, I offer you the cities of Baltimore, Chicago, Atlanta, and New York (to name just a few) as places that would benefit from your love and attention. If peace is really the goal then we should start by promoting peace at home—in the cities across America where people are dying and starving; where they are unemployed and underemployed; where our kids are dropping out of schools or spending countless hours playing senseless violent video games and listening to violent misogynistic rap lyrics; where folks live in sub standard housing within food deserts; where murder, violence, rape, drugs, crime, and gang activity are accepted as normal behavior; where the classroom to prison pipeline has yet to be disrupted; and, where conscious people are working hard to try and raise healthy, happy, and whole children. We cannot promote peace abroad if we don’t live it at home. I urge you to reconsider your position and remember as one wise sage once said, “If you want to make the world a better place, take a look at yourself and then make that change!”

August 31: To be clear: I am not naive. I know that violence is a part of the world that we live in but I will never ever believe that war is an answer for anything, particularly in this case. Although the Bible refers to us as sheep, we do not have to blindly follow our government. We can question their policies. We can hold them accountable. We can be conscientious objectors…perhaps if more individuals around the world stand up and speak out, we can force our leaders to think through their decisions. I sometimes wonder if making a decision to go to war would be more difficult for our leaders if it meant that they would have to be on the front line.

So in the midst of all of the ongoing conversations about war and violence and destruction, what can I leave my sons…well, I leave them this poem:

———————–

If I allow my sons to spend most of their hours playing violent video games, how can I expect for them to spend the rest of their time working for peace and justice

If I allow them to engage in unhealthy activities that contradict and interrupt the healthy activities they should be involved in, how can I expect them to be able to create a better world

If I never tell them no or teach them about peace and love, how can I expect them to be patient and to work to make the world better for others

If I teach them that their talents were given to them to make their lives better, how can I expect them to understand that “given” means “entrusted” and their job is to use their talents to make the world better

If I condone violence in any form and allow them to take pleasure in video games where satisfaction and points are tied to the number of people you kill, how can I ever expect them to see all people as extended members of our family and not as targets

If I sit back and allow them to wordlessly digest images of sex and violence and torture and inhumanity as easily as they digest their peas and corn then I must be held responsible for the actions that happened as a result of the seeds I have planted.

Related articles

- Pope Announces Day of Fasting for Peace for Syria (maboulette.wordpress.com)

The Power of Change (Or Life After the Release of the Sex Tape & the Open Letter)

©2013 by Karsonya Wise Whitehead

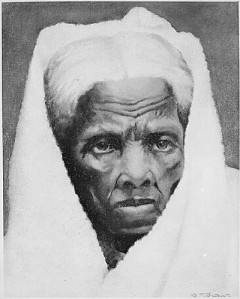

It has been over 150 years since Harriet Tubman helped to lead her family and friends to freedom. Her legacy and her name have been remembered and have been taught to every generation since that time. She is a part of the American culture, as her work and her contributions during the period of American enslavement, the Civil War and the Women’s Movement, stretch beyond the African American community. She helped to make our country a better place and for that we should be eternally grateful. When people like Russell Simmons seek to change and tarnish the memory of our American heroes, those of us who are conscious and who are active must speak up and lean into the space in an effort to bring about change.

On August 19, 2013, Judith G. Bryant, the great great grandniece of Harriet Tubman, reached out to me to share her concerns about Russell Simmons’s decision to release the sex tape video and his subsequent “apology.” We shared both our mutual feelings of disgust, anger, and sadness and concern that this false information has now become a part of our public consciousness and is forever linked to the life and times of Harriet Tubman. We exchanged materials: I sent her a link to my blog post about Harriet Tubman and she forwarded me a copy of her letter to share with others. With her permission, I posted the Open Letter on my website and it has since gone viral: http://www.academia.edu/4273201/An_Open_Letter_to_Russell_Simmons_from_Harriet_Tubmans_Great_Great_Grandniece.

My hope is that by speaking up, people will recognize that silence is never the answer and that change, if you push hard enough, will eventually come.

****************

I. On Russell Simmons, Moses, and the Push for Freedom

It takes a lot for me to be surprised by what people say and do, as I usually expect the best from people and am disappointed (but not surprised) when I do not receive it. I pride myself on being a fair person who gives people the benefit of the doubt. I try to see people for who they are and I do my best to accept them despite their obvious faults and flaws. At the same time, in this age of technology and reality television, I know that people will do and say just about anything for money and fame. Even though I do not agree with the way the world is moving, I do accept that it is moving and that I need to make decisions about how much I want to move with it. I am a realist and somewhat of a pragmatist having grown up between Washington, DC, where I was surrounded by forward thinking black people, and South Carolina, where I visited stores that still had their “For Colored Only” signs taped to the wall. As a historian who studies black women’s history and as a Christian who has read the Holy Bible more than once, I feel that I have read so much material (on topics that range from rape to slavery, incest and war, physical abuse and domestic violence) that my heart is almost hardened to the realities of this world.

And yet, I found myself surprised, shocked, and hurt by Russell Simmons’s recent Internet release of a Harriet Tubman sex video: http://www.wwtdd.com/2013/08/the-harriet-tubman-sex-tape-was-a-huge-success-video/. As I sat there, watching this distasteful clip, tears were rolling down my face as the young actress portraying Harriet Tubman began to seduce her plantation owner and joke about how she much she enjoyed their secret times together. I was (and still am) angry at Russell Simmons and people like him who are willing to do anything for money. I felt sorry for the actress and the other actors who agreed to be a part of this project and I believe that they also should be ashamed, shamed, and embarrassed.

As I sat there, shaking my head, I realized that in this age of technology, no matter how much you sacrifice to make the world better you can still end up as a star in someone else’s sex tape. I have never been a Russell Simmons fan but after watching the video, I spent countless hours trying to find out more about him as I needed to understand what would compel a sane person to support, fund, and promote this type of work. I realized that Simmons, like most people in America, either does not know his history or does not value it–because at some point, your life should be about more than wanting to make money (though he seems to do that very well), it should be about making the decision in your spirit that there are some things that you will never do just to make money.

Excerpt from “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post-Racial America” (Apprentice House, 2015) https://www.apprenticehouse.com/?product=letters-to-my-black-boys-raising-sons-in-a-post-racial-america

Harriet Tubman photo: http://www.mchenrycountyturningpoint.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/harriet-tubman.jpg

Excerpt from “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post-Racial America” (Apprentice House, 2015)

©2013 by Karsonya Wise Whitehead

For the past couple of months, I have been thinking about what lessons I wanted to teach my 12-year old son, as he is on the verge of becoming a teenager and his life is changing in so many ways. I thought that my blogs would be about love and relationships, friendships and heart breaks, dreaming and working towards your dream. My plans changed after the Zimmerman verdict was released. I wrote about it on my blog and then I sat down with my husband to discuss why it was time to have the “talk” with our sons. My youngest is 10 and we felt that he needed to be a part of this conversation. Although both of them are familiar with the events that happened during the Civil Rights Movement, we don’t believe that they are as well versed about current racial issues as they need to be. In some households, “the talk” is about sex, abstinence, protection, pregnancy, and making good decisions. In our household, “the talk” is about race relations, the perceived criminality of black men and boys, gang and drug violence, and the unwritten crime of walking while black.

We then decided that we would share our thoughts about having the “talk” with the world and submitted our “Open Letter to Our 12-year Old Son” to The Baltimore Sun. It was published on July 21, 2013 and has been shared more than 200 times, tweeted more than 70, and recommended more than 140 times. It also received 85 comments, some of them were extremely negative while others were both positive and supportive. We chose not to respond to any of the comments but to let our Letter speak for us. We are (like many parents) trying to do the best that we can to raise two young men who will be happy, healthy, and whole. We want them to be the best of what they can be and use the talents and gifts that God has entrusted in them to make the world a better place. Our hope is that the world will change and that they will be the last generation to ever have to have this “talk.”

“AN OPEN LETTER TO OUR 12-YEAR OLD SON”

By Johnnie Whitehead and Kaye Wise Whitehead

When you were a little boy, whenever you started crying, we would put you in your car seat and take you for a drive through downtown Baltimore. We would play Sweet Honey in the Rock and sing out loud until you started moving your head, clapping your hands, and singing along. You grew up on folk music and freedom songs, and though you did not understand them, we had always hoped that the meaning of the words would someday make sense. We vowed, as all parents do, to protect you and to do all that we could to make the world a better and safer place, where you could grow up and be free.

We have done all that we can for you and your brother, and yet, in so many of the ways that are important, we have failed you. The world is not a better place. It is not safer, and people are not equal. We are still being judged (and judging others) by the color of their skin rather than the content of their character. We have not gotten to the Promised Land and are really starting to question whether that land actually exists.

We are the parents of two African-American boys, and every day that we leave the house, we know that we could becomeTrayvon Martin‘s parents.

We are aware of how difficult it is to raise an African American boy in this city and in this country. We are familiar with the stereotypes and the racial profiling and have read and studied cases where young, black men are always assumed to be guilty and then must prove their innocence. We know that gun homicide is the leading cause of death of African-American males between ages 15-19. Your father and your grandfather have experienced more times than they would like to admit what it means to be reminded that you are black and male — and therefore you are dangerous and criminal.

Excerpt from “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post-Racial America” (Apprentice House, 2015) https://www.apprenticehouse.com/?product=letters-to-my-black-boys-raising-sons-in-a-post-racial-america

Letters to My Tweenage Son (Part II)

©2013 by Karsonya Wise Whitehead

2. On Believing in Freedom & Making the Choice Not to Rest* (Or Life After the Zimmerman Verdict)

“Motherless Child” Ronell Nealy Tru Art Media

Dear Buddy:

My favorite moments with you happened when you were a small child. I used to sit with you in your room and play music by Sweet Honey in the Rock. You used to sing with me as we danced around the room, shaking our heads, and clapping our hands. I remember one day when I was singing the words to “Ella’s Song” and I started to cry. We were sitting in your room and you came up to me and grabbed my hands and wanted to know why Mommy was crying and singing. I put you on my lap and just held you tight because I knew that in so many ways the words to that song had to be my rallying cry. I was the mother of a young African American warrior and if I believed in freedom and if I wanted the day to come when the “killing of black men (black mother’s sons) is as important as the killing of white men (white mother’s sons),” then I, as an activist and a mother, could not rest.* I had to use everything that I had (all of my talent, my time, and my energy) to help create a world where you could grow up and be free. Your father and I have done all that we can for you and your brother and yet, in so many of the ways that are important, we have failed you.

II. Trayvon Martin: Yesterday, Today, & Tomorrow

I have spent the last few days thinking about Trayvon Martin, Emmett Till, the four little girls, Yusef Hawkins, and the thousands of nameless faceless children who were the victims of the senseless violence that grew (and grows) from the roots of racism. I have cried and yelled, prayed and mediated, and then I did what I do best and that is simply grabbed my pen and wrote. I must admit that up until the moment that the Zimmerman verdict was read aloud, I still believed that justice would it be served. I followed the case as closely as I could and I did my best to explain it to you while trying to protect you from it. I read all of the articles and listened closely to the testimony. I tried to understand George Zimmerman’s version of the truth and tried to look past both the “Knock Knock” joke and the lack of diversity amongst the jurors. I defended the witnesses and even though I felt that some of them were not properly prepared, I believed that the jurors would be able to look past all of the “errors” and see the truth. I remember when I first heard about Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman and about what had happened on that night. I was outraged to find that on the night that Zimmerman shot Martin, he was quickly released from custody. When he was finally arrested and charges were filed, I breathed a long sigh of relief. I called your grandfather and he reminded me about how black people over the years have been and are severely disappointed by the judicial system. He felt that justice would not be served and that we would find ourselves back at the beginning of the struggle, yet again. I heard him but I chose to believe. We are Americans and though this country has let us down so many times, I still believe in it. I still believe that we are going to get beyond race and become the country that I have always believed that we could be. We got through the Revolution, slavery, Jim Crow, and the suffrage movement, and someday we will get past this thing called race. I thought that we would get past it before you grew up but I was wrong.

III. A Mother and a Her Child

At this moment, I am writing to you because I am hurting and I am scared. In the past couple of months, our nation has changed and is changing so quickly that I feel that all I can do is just tread water. I write to you tonight because young men who look like you are dying at alarming rates, some at the hands of white vigilantes and some (too many really) at the hands of other black men. I write to you because I fear that I have not properly prepared to do the type of battle that you are going to have to do to make the world better for your children, my future grandchildren. I am writing to you because I am trying to find the words to apologize for being a part of the generation that has failed you. We have dropped the baton and have not done our part to make this world a better place.

Your generation, my son, has been coddled and spoiled and has probably never actually heard the word no. We made you believe that you were the center of the universe and have therefore not prepared you for battle. I remember the first time you swung the bat in T-ball and hit the ball out past second base. You were so excited that you ran around the bases, twice. I shouted and screamed and Daddy carried you on his shoulders. We celebrated your first homerun with milkshakes and a special dinner. We called everyone we knew and told them about your amazing homerun. We were so excited that we convinced you that every time you swung the bat, you would hit a homerun.

IV. Baseball as a Metaphor for Life

As life would have it, at the next game when you came up to bat, you kept swinging but you could not hit the ball. You were devastated and we had a hard time explaining to you that we were wrong because every swing was not going to result in a homerun. We were unable to convince you and for the rest of the season, you kept expecting to hit a home run and you were incredibly disappointed when you did not. As you have grown up over the years, we have tried so hard to teach you that life is not measured in home runs but in getting back up to bat again. We were talking about baseball but also about life. You will strike out and you have to learn how to move past it, put it behind you, and pick the bat up over and over again. I have shared all of my home runs with you but I have shielded you from my strikeouts. Today I wish I would have shown you every rejection letter rather than the published, polished articles or shared with you how disappointed I was when I was rejected rather than how elated I felt to be accepted. I told you all about how happy I was when I pledged Delta but never mentioned how hard it was when I was rejected the first time I applied and all of my friends pledged without me. You were there when I spoke at the White House for the Black History Month panel but I never told you how nervous I was every single moment of every single day that I would not say the “right” thing. You see me walk around with my head held high but you do not know how often your grandfather—when I was teenager—had to grab my chin, lift my head, look me in the eye and remind me of how special I was. You always smile when your Daddy tells me how much how much he loves me but you do not know how many times I have heard those words from men who did not love me or, in some cases, did not even like me. You attend an independent school but you are not aware (though I am and your grandfather is) of how long it took before schools like that accepted boys and girls who look like you. You are not prepared to do battle because I have tried so hard to convince you (and myself) that every battle had been fought and had been won.

V. Freedom’s Song

My son, I am a child of the Civil Rights Movement and I have had some incredible shoes to fill. I grew up listening to the stories and benefitting from the work, but I (and those who grew up with me) never experienced separate water fountains or being forced to sit in the back of the bus. I grew up seeing people who looked like me in positions of power. Your grandfather committed his whole life to helping to create a world where despite the color of my skin, my gender, or my economic standing, no door would ever be closed to me. He was part of the nameless faceless masses who marched behind King and sat down at lunch counters, boycotted public transportation, sang and prayed and hoped for changed, was arrested and held overnight in prison cells, and was called the n-word more times than they would like to remember. And despite all of the odds against him, he helped to change the world. He was born in Lexington, South Carolina on a farm with an outhouse, miles of land, and a lake that set at the bottom of the hill at the edge of their property. He picked cotton over the summer, taking long rest breaks to read his book, one chapter at a time. He had one suit, white. When his mother, my dear sweet grandmother Marie, bought it for him on sale, it was too long and too big so they rolled both the pant legs and the sleeves up. Every year, he would roll it down until the year that he was able to see both his ankles and his wrists. He remembers having to walk past three schools to get to his one room schoolhouse. He used to tell us how in the winter the students would crowd around the big black stove that sat in the middle of the classroom and how in the afternoons, everyone would move closer to the window to capture the light so that they could finish their work. He loved going to school because the teachers (all of them black and female) would tell him that the only way that the world was going to change was by him choosing to be a change agent. He had big dreams and he knew that the only way to make those dreams come true was to fight and sacrifice over and over again. He made a vow that his children would never have to experience life like he did, and we did not.

We vacationed in a RV every summer. My father would pick a city on the map and we would drive there and park in the parking lot of a fancy hotel. We would eat in the hotel’s restaurant and swim in the pool without having a care in the world. I was sent abroad for the first time when I was in the sixth grade. I attended an advanced academics school (they called it a “school without walls”) and our class trip was to Canada to see Niagara Falls. I remember sitting in class one day when my classmates who sat by the window yelled out that my daddy was there and was getting out of a white car wearing a white suit. They said he looked like a pimp, to me he looked like my knight in shining armor. He came upstairs and paid for my $600 trip in cash. I remember because he paid in five and ten dollar bills. Your grandfather used to own a gas station and used to work the night shift so instead of going to the bank to make his morning deposit, he came to my school to pay for my trip. I have never believed that any door was ever closed to me. I was my father’s daughter and I understood that I was benefitting from his work. I was able to live the life that he had always dreamed about. I knew that he struggled. I knew that he sacrificed. I knew that I was not entitled to these rewards but that my father had earned them for me and was giving them to me.

VI. Going Forward From Here

When you were growing up, I did not share these stories with you on a regular basis. I never made you learn the words to “We Shall Overcome,” though I had to sing it everyday when I was in school. I never made the struggle real to you although I did talk to you about it. You have been raised in a privileged environment, have traveled extensively, and have met people from all over the world. You have no idea of what it means to struggle. You have never been made to feel invisible and have never felt profiled or threatened. I have tried to protect you when I should have prepared you. Beloved, you are strong and smart, brilliant and funny. You are the next generation and the blood of every one of our brave and courageous ancestors flows through you. Now that the jury has spoken, your father and I will turn our attention to speaking to you and your brother everyday about what you need to know and what you need to do to navigate your way through this world. It will be a better place but you will create it and where I (and those of my generation) have failed, you will succeed. I look forward to being there on that day and to celebrating with you…

Until

Mom

My young warrior activists…many many moons ago

My young warrior activists…many many moons ago

*Sweet Honey in the Rock, “Ella’s Song,” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6Uus–gFrc

Letters to My Tweenage Son

Mother and Son

©2013 by Karsonya Wise Whitehead

1. Nurturing Masculinity

Dear Buddy:

I watched you earlier this year at your first boy/girl mixer, as you were walking around with your hands in your pocket looking a little confused and unsure. I saw the girl that you like and I saw you follow her around the gym; looking for opportunities to say something to her, finding ways to touch her arm or grab her hand. I saw you try to dance with her and how the two of you, slightly embarrassed, decided to call it off and to just stand and talk instead. I saw the way you stood when other boys came over and tried to get her attention. I saw the protective shrug of your shoulders as if you were staking claim, letting them know that this space was your space. You did not know at the time but my eyes never left you. You were growing up right before my eyes. In so many ways, you are still my little baby boy who needs to be fed and carried, changed and comforted. You are my firstborn and everything I learned about being a mommy, I learned from practicing on you.

As I watched you that night, I realized that you are on your way to becoming the man—the person—that I had always hoped you would become. I have done (and will continue to do) everything that I can to nurture you. You once asked me what a feminist looked like and I–partly in jest—stated that if I have done my job right, you will see a feminist every time you look in the mirror. I laughed when I said it but later, after I had had a moment to reflect, I realized how much truth there was in that statement. I am raising you to believe in and defend equal political, economic, and social rights for women. At the same time, I am also raising you as a Christian. For some this may seem like a contradiction but for me, I can not imagine sending you out into the world without having deep roots in both of these areas. My hope is that this grounding and teaching will help you as you decide how you are going to see the world and your place in it.

As you and your friend made your way around the gym, talking and laughing at jokes only the two of you could hear, I realized that you were at the beginning of a dating ritual that goes back much farther than you or I and will now be a part of your life up until you get married.

I do want to caution you because it quite possible that she will break your heart. I say that not because I want your heart to be broken, but because I know that you are only twelve. You have a long way to go before you really understand what it means to fall in love and to commit your life to just one person. You are at the beginning and in so many ways; the beginning is really a good place to be. As you stand here, at the threshold of your unknown, I wanted to offer you some relationship advice that I hope will act as a compass to help you navigate yourself through this well-worn journey:

1. Be kind to her and treat her well. Just like you, she has parents who love her and believe in her. She is your equal, not your property, so give her the space to speak her mind and the ability to change yours. Treat her with as much dignity and respect as you treat me.

2. Make her laugh and enjoy laughing with her. There is nothing more comforting than being around someone you can laugh with. Laughter is a balm and a healing salve. Trust me, as you get older, there will be days when laughing will keep you from walking out of the door or from saying something that you can never take back.

3. Guard your heart and guard hers. You have been raised well and have been treated well. You know what it is like to be appreciated and supported and loved. Do not expect, accept, or offer to her anything less than that.

4. Be nice to her mother. Even though mothers are not perfect, some of us work very hard to give our children choices. We sacrifice over and over again to give you the best that we can afford. We try to raise you in such a way that you will have more victories than defeats, more friends than enemies, and more opportunities than regrets and after we have done all of that, we realize that all we have left is the ability to pray our heads off and hope for the best. Treat her mother as you would like for her to treat me.

5. Get the door for her, pull out her chair, and pay for everything on the first date (and I am smiling as I write this). I know that these are old-fashioned “male” values and that they probably go against everything I have done/said to raise you as a feminist; but, there is still something in me that enjoys those things. I call it two-sided feminism and I struggle with it everyday. I know that you know that women are equal and that we can get our own doors, pull out our own chairs, and pay our own way but I must admit to you how nice it is to come across a guy who cares enough for you to want to do those things for you.

6. Resist the temptation to make her your entire world. Although there may be days when you feel like the sun rises and sets only on her, it does not. As special as she may be, she is still just a part of your life and not your life. Furthermore, do not allow her to make you her world for heavy is the burden of being the only one responsible for making someone happy.

7. Be as honest as possible with her and with yourself, as there is nothing more painful than ambiguity from someone you think you like and who you think feels the same way. If you do not like here, then let her down easily and let her go. Allow her to move forward to find someone who will adore and cherish her.

8. Be a man of your word and if you say you are going to call or be there or do something, then just get it done.

9. Be good to yourself and be good to her. Even though this is probably not the girl that you are going to marry, you still want to leave her with fond memories of you. Your grandfather used to tell us to leave people better than when we found them, to not pull them down, or intentionally hurt them. You want to pull her up and build her up. You want to make her feel that she is visible and that she is important.

10. Be patient with her, with your relationship, and with yourself. Love takes a long time to grow. It must be nurtured and tended to and sometimes it must be left alone. You cannot rush the process nor should you have to.

11. Do not settle for anyone other than the best person that God has for you. Your father and I are pouring everything we have into you because we love you and we see your potential. In our eyes, you are a diamond and we are responsible for brushing off the dirt to help you to shine. It is not always easy for you to see your own potential or to believe that you are special but, in those moments when you cannot believe in yourself, believe in us because we believe in you. Sometimes, just knowing that someone believes in you will help you to make it through the darkest of days, the loneliest of nights, and to make the best decision.

12. Put God first. I saved this one for last because this is the foundation that everything else must be built upon. You are being raised in a Christian home and it is a part of who you are. As you make decisions about “who” to date and “when” to date and sometimes even “why” to date – my prayer is that you filter all of these questions through the lens that your father and I have given you. (I know that like me you will come to a point where you will make a decision about what you believe and about whether you want to live your life as a Christian –when you get to that point, know that I will be there with an open heart, a supportive word, and a patient spirit to either advise you or support you in whatever decision you make). My hope is that Christ is involved in every decision that you make. So..if you want to ask her out, I hope you pray about it. If you want a second date, then I hope you pray about it. If you want to ask her to marry you (or she has asked you to marry her) then I (really) hope you pray about it. And then, when you get married, I hope that like your father and I, the two of you start praying about everything—together.

You, my dear sweet son, are at the beginning and even if I wanted to, I cannot protect your heart from getting broken. All I can do is love you, support you, and do my best to help guide your ship into its port. The road will be long, but with good guidance and a lot of prayer, you will find the girl that is meant for you. I look forward to being there on that day and celebrating with you…

Mom

The Cancer Journals (Excerpt from “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post-Racial America” Apprentice House, 2015)

©2013 by Karsonya Wise Whitehead