“Black Women’s Equality Day,” was July 31; Dr. Karsonya Wise Whitehead wants America to pay up.

Reflections: On Being Selected to Essence’s 2019 Woke 100 List

#RedNanaDrops

So who do you write for? Who do you protest for? Who do you struggle for? Who gets you up in the morning? Whose voice do you have in your head? Who is the wind beneath your wings and the hand that pushes you forward? Who do you look for when you want to hear the words well done?

~For me, it was my Nana. I loved her so much. She encouraged me. She admonished me. She pushed me. She laughed at and with me. She told me my truth. She sang the songs of my soul. She knew who I wanted to be long before I could articulate my being to myself. She made me acknowledge when I was wrong and celebrate when I was right. We used to read the Essence magazine while we were standing in line. Once in a while, we would buy a copy and I would put my picture between the pages and pretend that I was between the fold. I used to write out an interview, detailing all the wonderful things profiled in the article: that I was changing the world, I was a trendsetter, my voice spoke volumes, I was brave, I was unashamed, I was beautiful. She would always say that I was already all of those things, the world just needed to catch up and see me.

~Six years ago today, this week, my Nana died. She ran on home to see how the end is going to be. This is also the week that I made it to between the Essence fold. Oh how I wish she was here to see it so we could laugh about it, cry about it, and just be in the same space together. My heart is heavy because a piece of it is missing.

Essence link: https://www.essence.com/news/2019-woke-100/#474573

Baltimore Sun article: https://www.baltimoresun.com/features/bs-fe-whitehead-essence-20191028-6wfcfx4kybb47kkpvtqlhdraqm-story.html

The Supreme Court ruling is just the latest version of a question that the Whitehead family — and the nation — has been grappling with for years: How to deal with the legacy of slavery?

Amir Whitehead felt that ending affirmative action was not wrong. Other family members felt differently. Credit…Bryan Anselm for The New York Times

For the Whiteheads, an African American family living in the city of Baltimore, race is discussed at the dinner table. In the car on the way to work and school and games. In the backyard while the sons practice sports.

So when the Supreme Court struck down race-conscious admissions at colleges and universities, effectively ending the practice known as affirmative action, the family began talking about it earnestly, echoing the range of emotions felt by people across the country who are invested in the ruling.

Though the result was anticipated, Karsonya Wise Whitehead, 54, a college professor, said she was so devastated that she had to sit down to process “the type of history being made at that moment.”

Her husband, Johnnie Whitehead, 59, the principal of a Christian school, said he took no joy in the ruling but was ambivalent about affirmative action. He is hopeful that it is no longer needed, but fears it is.

The eldest son, Kofi, 22, texted his brother Amir to share the news, and thought of the chilling effect it might have on the next generation of Black students. Amir, 20, felt that ending affirmative action was not wrong because admissions should be based upon merits only.

For the Whiteheads, the Supreme Court decision — seismic in its power to reorder the admissions process at elite colleges and universities — was another chapter in a broader discussion they had been having since their children were young.

Their conversation reflects, in some ways, the complex and shifting views among African Americans grappling with the question embedded in the nation’s every contemporary racial conflict, from reparations to the American justice system: How to deal with the legacy of slavery?

Karsonya Wise Whitehead, a college professor, said she was so devastated when she heard about the Supreme Court ruling, that she had to sit down to process “the type of history being made at that moment.”Credit…Shan Wallace for The New York Times

“This is part of our ongoing conversation about the tensions around racism and around race,” said Dr. Whitehead, who teaches African American studies and communications at Loyola University Maryland and is the executive director of the Karson Institute for Race, Peace and Social Justice at the college. “We’ve seen different iterations of: ‘What does it mean to be Black in America? Where do we fit into America? Whose America is this? And if we want to have equity, what does this equity look like?’”

The family’s early talks centered on making sure their sons were confident in who they were as young Black men. That gave way to other topics.

Kofi favors reparations but doesn’t know what the right amount of money should be for Black families whose ancestors were enslaved. Amir favors reparations in some form, too, saying, “We built this country, we deserve some part of it.” Dr. Whitehead is not only in support, but she believes it is the only way forward to address the historical debt. Mr. Whitehead said Black Americans deserved reparations, particularly since the country had paid others that it harmed, but did not see it as a way to solve racism.

When it comes to affirmative action, African Americans are broadly supportive of the policy.

According to a Pew Research Center report released last month, only 33 percent of American adults approve of race-conscious admissions at selective colleges. Forty-seven percent of African American adults say they approve.

The research also revealed that 28 percent of Black adults said others had assumed that they benefited unfairly from efforts to increase racial and ethnic diversity.

A separate NBC poll in April found about half of Americans agreed that an affirmative action program was still necessary “to counteract the effects of discrimination against minorities, and are a good idea as long as there are no rigid quotas.” Among African Americans, the number in support of that statement increased to about 77 percent.

The starkly different attitudes toward the merits of affirmative action were laid bare most profoundly in the words of the only two Black justices. Their written exchange mirrored how the landmark decision was discussed, debated and deconstructed among friends and families — including the Whiteheads — at dinner tables, in group chats and on social media.

Justices Clarence Thomas, who attended Yale, and Ketanji Brown Jackson, who attended Harvard, challenged each other’s views, agreeing only on the existence of racial disparities but sharply disagreeing on how to address them.

“As she sees things, we are all inexorably trapped in a fundamentally racist society, with the original sin of slavery and the historical subjugation of Black Americans still determining our lives today,” wrote Justice Thomas, the nation’s second Black justice and a longtime critic of affirmative action.

Justice Jackson, in her dissent, said Justice Thomas “is somehow persuaded that these realities have no bearing on a fair assessment of ‘individual achievement,’” she wrote. In her opinion, the court’s conservative majority displayed a “let-them-eat-cake obliviousness” on the issue of race.

Johnnie Whitehead, the principal of a Christian school, said he took no joy in the ruling but was ambivalent about affirmative action. Credit…Shan Wallace for The New York Times

In some ways, the Whiteheads’ views of affirmative action aligned with both of the justices’ argument outlined on the pages of the ruling.

For Dr. Whitehead, a radio show host, author and the daughter of civil rights activists, the dismantling of affirmative action — rooted in the civil rights movement as part of federal policy to counteract discrimination — was a “gut punch.” She said she personally benefited from affirmative action as the first Black student in the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies program at the University of Notre Dame. She worries that the decision portends what is to come, shaping other aspects of life, including corporate hiring.

Mr. Whitehead said he understood the practice as a way to counter discrimination and mistreatment of African Americans. And, he said, if affirmative action is going to be abolished, legacy preferences should go, too.

“I’d like to believe that we are a nation that doesn’t have to have affirmative action, but I fear we still need it,” said Mr. Whitehead, who is also a teacher at Baltimore School of the Bible.

Kofi, the eldest son, who graduated from Rhodes College in May with an English degree, has a sensibility closer to his mother’s. He first began following the issue in high school after learning about a white student in Texas who sued the University of Texas at Austin for its use of race in admission decisions.

He sees last week’s ruling as both out of touch with the pervasiveness of modern racism and a blow to future generations of Black students looking to attend elite schools. And he chafes at the argument that college academic standards are lowered to create diverse campuses.

“Affirmative action is about opening the door to diverse backgrounds because that is what education and higher learning is about,” Kofi said. “It’s not about having 5,000 of the same kids in two-parent households and white picket fences who all come in and do the same thing. No. College and higher education is about bringing in different people so you can learn from each other.”

His younger brother Amir, who is a member of Lafayette College’s fencing team, sees it differently. A college sophomore who is studying economics, he began developing his political and socially conservative views as a middle school student during the presidential race between Hillary Clinton and Donald J. Trump.

Kofi Whitehead, seen on the campus of Rhodes College, says he worries about the negative effect the court’s affirmative action decision might have on the next generation of Black students. Credit…Priscilla Foreman

While he and his mother’s views are the farthest apart, she said he was raised “to be an independent thinker.”

He agrees with the other members of his family that race, and the nation’s history of enslavement of Black people, undeniably affects the present day. But, he said he believed that affirmative action undermined the concept of earning admission based on qualifications rather than race.

“Affirmative action being taken away is not so much a bad thing, because I don’t think that anyone who is not qualified for something should get that purely based off their skin color,” said Amir, who noted that he included his race on his college application but did not include the subject in his personal essay.

“I am not saying the bar has been lowered,” he said. “I just feel as though sometimes, cases come down to race. I think that goes back to us, as a country, where everything is focused on race.”

A version of this article appears in print on July 3, 2023, Section A, Page 13 of the New York edition with the headline: A Black Family, Split On What a Key Ruling On Admissions Means. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Reclaiming My Time & My Money (Afro OpEd)

Two days before my birthday, and I was reminded all over again that I am a Black girl in America and that means something. I was seven years old the first time I was told this reality. I had spent the afternoon fighting my boy cousins and beating them in foot races through the woods. They were wearing shorts and I was wearing a skirt that I had tied between my legs like makeshift bloomers. My grandmother called me over and told me that I needed to start acting like a lady which meant that I had to stop fighting and racing. I had to clean the dirt off my face and start getting my hair pressed. I had to learn how to set the table and wash the dishes; how to sew, and hem, and iron sheets. While my boy cousins fished and built sand castles, I learned how to wash clothes and make the bed. I used to look at them out of the window, wishing that I could be a boy so that I could be free. This is the first time when I felt like I could not breathe. There was a feeling of anomia where I knew what was happening to me but I could not name it and none of the women in my life seemed to have the capacity (or words) to say it out loud. This feeling of gender inadequacy was reinforced in my church where I learned over and over again that the sin that plagued and infected our world came from a woman who dared to make her own decision. It took me years to become a Black feminist, to be able to recognize my gender and racial oppression and fight against it; to stop thinking that I had to be twice as smart as White people or work twice as hard as a man, to stop measuring myself against them as if they were the standard. This is what true internal oppression looks like when it is formed and shaped over a lifetime by a coagulation of feelings, emotions, subtext, inequality, intentional erasure, and perceptions of inferiority.

Most days I am able to balance my anger at the system with incredible moments of joy but there are some days that are more difficult than others. Black Women’s Equality Day is one of those days. It is the one day where I am brutally reminded that no matter how hard I work or how many degrees I have or how many pay raises I receive, I still have to work an extra six months to catch up to my White male peers. It is a race that I will never win or tie as it is designed for Black women to lose. It is a very blatant reminder that Black women, as Zora Neale Hurston once wrote, have always been and continue to be the mules of this world. We stand tall and yet, this 37 cents difference only shows us that society continues to benefit from riding the backs of Black women and exploiting our labor.

There are approximately three million American families that depend on the income that Black mothers earn and with this pay discrepancy, households are suffering. The tentacles of economic oppression find their way into every aspect of a Black woman’s life, from mortgage payments to childcare; college savings to purchasing healthy food. At this rate, it would take a Black woman about 108 years to catch up and achieve wage equality (this is assuming that the pay rate for White males remains constant) This is unacceptable. We must work together to reclaim this 37 cents and reclaim the time we spend into the system without being adequately compensated. It really does matter, and until it is done and the ledger is clean, both systemic oppression and racial inequality will continue.

Karsonya Wise Whitehead (kewhitehead@loyola.edu; Twitter: @kayewhitehead) is the #blackmommyactivist and an associate professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland. She is the author of “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post-Racial America” and “Notes from a Colored Girl.”

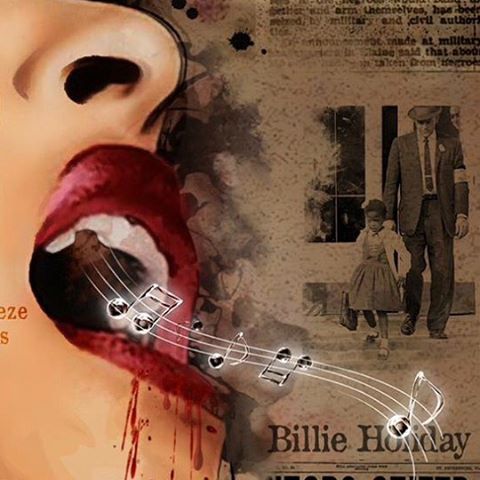

Blood On The Roots

Author and university professor Karsonya Wise Whitehead contemplated the concept of, “freedom,” as millions celebrated the Fourth of July.

I had a moment during Sunday service, when my pastor asked us to stand, turn toward the American flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. I cringed as everyone quickly stood, placed their hands over their hearts, and proceeded to recite the Pledge, without question and without hesitation. I sat there fighting against my desire to stand and be obedient because I knew that as a black person in America, I could not pledge my allegiance to this racist nation or to our bigoted president.

In psychology, they call this moment cognitive dissonance, which happens when a person is struggling with at least two contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values. I am a descendant of enslaved people who fought to survive in America and war veterans who died while fighting to protect America. I am a walking contradiction where my American racist values and my black consciousness and pride are constantly warring against one another. W.E.B. Du Bois called it double consciousness, an oppressive way of viewing and judging yourself, as a black person, through the eyes of a racist white society.

I thought about all of this as the Pledge gave way to the singing of, “My Country Tis of Thee,” because I believe that this America, this bastion of white supremacy, is not my ideal home. It is not where I feel safe or where I feel like I belong. I am the Sankofa bird who flies forward across this red, white, and blue landscape with rivers that run deep with the blood of innocent black and brown people, while hopelessly keeping my head turned in search of something else, of somewhere else. This feeling of black restlessness, despair, frustration, and anger are not new. It always feels like it is our blood that is on the leaves and at the roots, fertilizing the soil that feeds the American dream of white exceptionalism. We have long felt like we did not belong here.

Langston Hughes in his poem, Let America Be America Again, wrote “There’s never been equality for me, Nor freedom in this homeland of the free.”

But still, in church I wanted to stand, as this is what I have been taught to do by my father and obviously expected to do by my pastor. I wanted to be obedient and follow the rules.

I really want to be proud of my country and to celebrate her independence. I want to answer Frederick Douglass’ question, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” and tell him that although it has taken us 165 years, we have finally arrived. I want to say that the Fourth of July is now our holiday for we have been embraced and counted as part of the American dream; that we have been allowed to fully participate in the democratic process and have seen the day when a person is judged by the content of their character and not the color of their skin. I want to say that we have gotten past the racist notion that skin color is more important than skills and talent; that we no longer have to shout that, “Black Lives Matter,” for we have gotten to a point where those types of questions (about who matters and who does not) have been settled and that we have realized that we are stronger together as one nation than we are apart.

I want to say that but I cannot. I think of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling; Terence Crutcher and Korryn Gaines; John Crawford III and Eric Garner; Rekia Boyd and Aiyana Jones; Tamir Rice and Freddie Gray, and countless others. I think of their lives and of what we lost on the day that they were murdered. These are the moments when America — a beacon and shining light of white hope and pride — brutally reminds us that the Fourth of July is theirs and not ours, and as they celebrate, we must mourn. It is hard to pledge allegiance to a country that does not recognize your humanity. In 1852, Douglass noted that slavery was the great sin and shame in America; today it is oppression, and it is white supremacy, and it is injustice.

Karsonya Wise Whitehead (kewhitehead@loyola.edu; Twitter: @kayewhitehead) is the #blackmommyactivist and an associate professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland. She is the author of “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post-Racial America” and “Notes from a Colored Girl.”

Should God Bless America?

(Justin Sellers / AP)

by Karsonya Wise Whitehead (originally published in The Baltimore Sun, 7/2/17)

My entire life has been centered around the belief that God wants to bless America and that he is only waiting for us to ask.

Growing up as the daughter of a Southern black Baptist minister, my life was filled with church services, communion and prayer. I learned early how to get down on my knees at the end of every day and ask for forgiveness and ask God to bless my family and America. My dad is a veteran, having served during the Vietnam War, and he believed that we needed to remember that America was always primed to be attacked and that it was our prayers for her that kept her safe.

He was also raised in Jim Crow South Carolina and had been actively involved in the Civil Rights Movement, and he taught me that the America that we were asking God to bless was not the one that we saw in front of us, but it was the potential for what she could some day become. He said that when he would get arrested or spit upon or he was called the N-word, he would silently ask God to bless America despite the hatred and the inequality. When the Rev. Martin Luther King and President John F. Kennedy were assassinated, he told me that the only thing that got him through those days was prayer and asking God over and over again to overlook the sins of this country and bless us anyway.

We lived in a small black community in Washington, D.C., where most of my teachers were members of my church and when they spoke, in my mind, they had the authority of God behind them. Every morning, from 1st to 8th grade, we had to stand and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. We were “under God,” we were “indivisible,” and we did provide “liberty and justice for all.” As a young child, it made sense to me. America was the center of the world, morally balanced and uniquely charged with the task of saving and protecting the planet.

In history class, my teachers buried us in stories of dead white men, the vaunted Christian forefathers, who worked hard to craft a more perfect union, without teaching us that they were racist, sexist, classist slave holders. We never talked about what or who was missing from these great American tales of courage and valor, never questioned the validity and reliability of these stories. We simply accepted them as the truth, praying for and pledging ourselves to a nation that denied our humanity, that fought a war to keep us enslaved, that set up laws to keep us separate and was comfortable lynching, beating and oppressing us.

I was 5 years old the first time a president ended a speech by calling on God to bless America. It was 1973, President Richard Nixon in the midst of dealing with the Watergate scandal and trying to cover up his lies, ended a speech by saying, “Tonight, I ask for your prayers to help me in everything I do throughout the days of my presidency. God bless America and God bless each and every one of you.”

This was a watershed moment, when God entered the realm of politics and became both a shield and a weapon. As an American citizen, how do we begin to question the actions of our leaders when they invoke the name of God and call upon him to bless us? This phrase was not used again until Ronald Reagan, and since then every president, despite his actions, has called on God publicly to bless this country.

I know that God can, but I am wondering if he should. Should God bless America, a place where economic and social freedom only exist in the lives of a privileged few; a place where women and girls are routinely sexually assaulted; a place where black and brown people have to proclaim that their lives matter? A place where the current president is, by his own words and deeds, a bigot and a demagogue who tweets out hatred on a daily basis and whose election (America’s whitelash moment) ushered in a new age of divisiveness, racism, xenophobia and hatred — a man who ends every speech by calling on God to bless America?

By God’s own words, recorded in his holy Bible — where he calls on us to love our neighbor as we love ourselves, to practice radical hospitality, to be the good Samaritan, to shoulder one another’s burdens, to welcome the prodigal children home, to be kind and gentle and long suffering and peaceful, and to be slow to anger and quick to listen — America is not a country that deserves his blessing.

But then I think of my father and remember that we pray not for the ossified, divided America that this country is at this moment, but for the possibility of what she can become. And so, I will continue to ask God to bless America, while also advocating every day to change her.

Karsonya Wise Whitehead (kewhitehead@loyola.edu; Twitter: @kayewhitehead) is an associate professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland. A version of this editorial was aired as a public commentary on WYPR 88.1, Baltimore’s NPR station.

Changing the World, One Student at a Time (OpEd)

Karsonya Wise Whitehead; June 1, 2017 —Baltimore Sun Op-Ed

Achievement gap is our fault, not the kids’: Teaching is hard work, and teaching in the public school systemin Baltimore City sometimes feels like it is impossible. You spend time juggling classroom management, budget deficits and high teacher turnover while working in environments that are often dark and hot and crowded. It is not for the faint of heart.

I am a former Baltimore City middle school teacher who taught at a persistently dangerous school, and every day I walked into the classroom determined to teach my students that where they started in their lives did not have to be where they finished. I foolishly believed that their lack of educational achievement and success was simply a state of mind that they could change if they worked hard enough. I learned the hard way that I was wrong — that it’s everyone else’s state of mind holding them back.

On the first day of school I used to share a story with my students about my childhood dream of wanting to fly. I told them how I made myself a cape out of my sheet, jumped off of the fifth step and experienced pure joy for just a moment before I came crashing down. I kept it doing over and over again, until I realized that if I kept doing the same thing, the same way, then I would get the same result. So I had my father stand at the bottom of the step, and the next time I jumped, I flew into his arms. It was simple: I changed my thinking and then I changed my ending. I told that story, year after year, thinking that I was encouraging my students to push themselves to think about new solutions to age-old problems. The very last time I told it, I asked my students to tell me how they could apply this story to their life. Only one student spoke up: “Look around this classroom, around this school — it looks like a prison. We are not supposed to fly here. Ya’ll keep telling us to jump down the stairs, with the same dirty capes and the same stupid plans, but you are not trying to catch us.”

That was 10 years ago, and every year, after reading about the state of Baltimore City schools, I think about my former students and about what it must feel like to be a part of a larger failed educational experiment that has been starting and stopping in this country for over 250 years. We are in the midst of a crisis in black education that is tied to poverty and a legacy in discrimination, which has been in effect since 1740 when South Carolina implemented the first Slave Code, prohibiting enslaved persons from learning to read and write. By the end of the Civil War, among the nearly 4 million black people in America, less than 10 percent could read or write.

The biggest impediment to black literacy was the recalcitrant attitude of some white people who firmly believed that free or enslaved, black people were not citizens and therefore had no rights — a harsh and cruel reality. Whenever I shared these facts with my students, they complained and said that these were old boring stories that had nothing to do with them. But today’s injustices are rooted in yesterday’s systemic inequalities, which persist, along with the firm belief by some that black and brown people are still not entitled to have either rights or a voice.

Even though the cultural landscape of the country has changed, negative attitudes toward black children remain and their literacy rates have still not risen to the level of their white and Asian peers. According to the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress, only 18 percent of black fourth-graders are proficient in reading and 19 percent in math. Here in Baltimore City, which maintains one of the country’s highest per-pupil spending levels, there are six schools that do not have any students who are testing proficient in either reading or math.

Black students continue to be disproportionately impacted by the shortcomings in our public education system. It starts as early as pre-K, where black students make up only 17 percent of the student population but account for more than 70 percent of the yearly suspensions. We are at a moment where we spend more time teaching black kids to survive this world rather than teaching them how to thrive in it.

If we want to survive as a city and nation, then we must be willing to admit that this current crisis in black education is our responsibility. We must be willing to admit that the current solutions are not working and that the educational industrial complex must be dismantled so that real change can happen. We must be willing to work together to find new and innovative ways to educate our children. And, if we really want them to learn how to fly — to experience moments of pure joy — than we have to be willing to commit ourselves to doing everything we can to catch them, all of them, before they fall.

Karsonya Wise Whitehead is an associate professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland. She is the author of “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post Racial America.” A version of this editorial was aired as a public commentary on WYPR 88.1, Baltimore’s NPR station. She can be reached at kewhitehead@loyola.edu or @kayewhitehead.

On Watching My Son Discover His Blackness… (OpEd)

Karsonya Wise Whitehead

Originally published in The Baltimore Sun: “The uprising may be over; but the work is not,” April 27, 2017

My son was six years old the first time that he realized that he was black. He was in the first grade, attending a Baltimore City independent school, and one day, during recess, the boys in his class decided to make-up a game called, “Let’s Get the Black Boy.” Given that he was the only black boy in his grade and thus on the playground, he spent the hour running for fear of what they would do if they caught him. The entire ride home he peppered me with questions about what it meant to be black: Was it something that we chose to become, why did he choose to run, and what did I think they would do if they caught him?

It was a long night for me as I spent the evening writing down everything I wanted to say to the principal. I practiced in front of the mirror, and I worked hard to build up my courage so that I would have the words to say and the heart to say them. My father once said that the hardest parent of being a black parent is the moment you realize that in the face of injustice and racism, your silence will be seen as an act of betrayal, a sign of complicity, and you would forever wear it as a badge that marked your moment of weakness.

The truth of my father’s words has stayed with me, and the responsibility that it calls me to have gets more difficult as the world continues to turn. In 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois stated that the problem of the 20th century was the color line, which referred to the role of race and racism in history and society. Today, the problem of the 21st century seems to be a false sense of racial, social and economic equality that fosters a culture of complacency — and intolerance for those who attempt to expose the myth.

It has been two years since the Baltimore uprising that followed Freddie Gray’s death in the back of a police van, a pivotal moment in our city that shifted our focus and called us to action on long-standing problems plaguing our city. It was a time of real honesty where we collectively shared our ideas, frustrations, hopes and dreams for a better, more united Baltimore. Since then, life has settled back in to the familiar. The pockets of the city that have historically been economically stable are once again doing very well; the number of tourists coming in to the city has steadily increased, and museums, hotels, restaurants and real estate are all showing signs of growth. And the neighborhoods that suffered before the death of Gray continue to do so.

Crime is still a persistent and deadly problem: 2015 and 2016 were recorded as, per capita, the deadliest and the second deadliest years respectively in the city’s history, and 2017 has already logged 101 homicides as of Tuesday. High unemployment and poverty rates continue. The public school system is not improving, and with an ongoing budget deficit and looming teacher crises, this is not expected to change. The communities that were largely ignored and underserved have remained at the edges of both the city and our minds. We are still at a crisis moment, though it seems the public urgency to act has evaporated.

We must take immediate concrete steps to finally end this long and difficult battle to save our city. Among them:

• Reallocate city budgets so that we are spending more money on our students that we do on our police force;

•Offer more incentives and financial guidance to first-time small business owners to encourage them to open up grocery and convenience stores in their own neighborhoods;

•Redesign the police department’s Civilian Review Board so that it has a higher visibility, a larger working budget and can act as a more effective checks and balance system for internal affairs;

•Establish more job training programs for unemployed and underemployed residents and returning citizens;

•Accept that we must be the ones to police our own neighborhoods, to reach out to our neighbors and to hold them (and ourselves) accountable for what is happening in our communities.

It has been two very long years, and we must finally and completely choose the type of city that we want to live in and take the necessary action for change. We cannot be silent, lest it be seen by future Baltimoreans as our collective act of betrayal, a sign of our complicity that we would forever wear as a badge that marked our moment of weakness.

Karsonya Wise Whitehead is an associate professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland and the author of “Letters to My Black Sons: Raising Boys in a Post-Racial America.” A version of this editorial was aired as a public commentary on WYPR 88.1, Baltimore’s NPR station. She can reached at kewhitehead@loyola.edu or on Twitter @kayewhitehead.

Black Quilted Narratives

Summer Teachers’ Institute –Application

July 10-21, 2017

APPLICATION INFORMATION AND INSTRUCTIONS

Application Deadline: June 2, 2017

The BQN Summer Teachers’ Institute is designed principally for full-time and part-time classroom teachers and librarians in public, charter, independent, and religiously affiliated schools. Prior to completing an application, please review the letter outlining the project and thoughtfully consider what is expected in terms of residence and attendance, reading and writing requirements, and general participation in the Summer Institute and Teach-Ins.

Please note: The BQN curriculum is designed to engage, inspire, and educate the next generation of culturally responsive leaders and political activists using historical moments from the Civil Rights Movement. Therefore, this BQN Summer Teachers’ Institute is best suited for educators and school personnel who would have the creative freedom and initiative to incorporate civic, social, and cultural topics into their instruction.

SELECTION CRITERIA

A selection committee, consisting of the Co-Project Directors and the Master Teachers will read and evaluate all properly completed applications in order to select the most promising applicants. We will identify a number of alternates in case those selected are unable to attend. The most important consideration in the selection of participants is the likelihood that an applicant and their school, by extension, will benefit professionally. This will be determined by committee members and is based upon a number of factors, each of which should be addressed in the application essay. These factors include:

- Effectiveness and commitment as an educator, based upon years of experience and/or prior involvement with professional development activities;

- Intellectual interests, as they relate to the subject matter of the project;

- Special skills or perspectives that would contribute to the Summer Teachers’ Institute;

- Commitment to participate fully in the formal and informal collegial life of the project; and,

- Racial and economic make-up of the school, with a special interest in (but not limited to) educators who teach in a Title I school; and the likelihood that the experience will enhance both the applicant’s teaching and the students’ present and future school experiences

.

APPLICATION INSTRUCTIONS

Application packages should be sent to the National Visionary Leadership Project (NVLP) via email at kewhitehead@loyola.edu by June 2, 2017. Late applications will not be reviewed. Twenty-five educators will be selected to participate in the BQN Summer Teachers’ Institute. Successful applicants will be notified of their selection via email by June 9, 2017 and will have until June 16, 2017 to accept or decline the offer.

APPLICATION CHECKLIST

A completed application package includes the following:

- The completed BQN application form (see below);

- A résumé or brief biography that details your educational qualifications and professional experience (one-four pages);

- An application essay that includes the following (four pages maximum):

- Your reasons for applying to the BQN Summer Teachers’ Institute;

- Your interest, both academic and personal, in the topics we will be studying;

- The relationship between your professional responsibilities and the BQN line of study;

- Your relevant academic qualifications and/or experiences that equip you to do the work of the Summer Teachers’ Institute; and,

- What you hope to accomplish by participating, including any individual research and writing projects you foresee undertaking and/or curricular units you will create.

- The names and contact information for two references, one of which should be an administrator from your school. The two referees should be familiar with your professional accomplishments or promise, teaching and/or research interests, and ability to contribute to, and benefit from, participation in the Summer Institute.

APPLICATION

Part 1: General Information

Name: ______________________________________________________

Home Address: ______________________________________________________

Work Address: ______________________________________________________

E-mail: _____________________ Home Phone: _________________

Citizenship: If not U.S., please specify country, month and year U.S. residence began: ________________________________________________________

**This information will be kept private and confidential. This information will be used for payment purposes only.

Please provide your school name and address:

________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

Please provide your principal’s name, phone number and email address:

________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

How long have you been teaching? ________________________________________

What grade(s) and subject(s) do you teach? __________________________________

What courses did you teach this year and number of students taught? _______________

Please provide the name, email address and phone number for two professional references.

- ________________________________________________________

- ________________________________________________________

How did you learn about the NVLP BQN Summer Teachers’ Institute?

________________________________________________________

Part 2: Teaching Information How would you classify your school? (Circle all that apply)

Public School

Independent Religiously Affiliated Home School

Charter School Elementary (K-5) Middle School (6-8) High School (9-12)

School Position (circle all that apply)

Full-Time Teacher Part-Time Teacher Classroom Professional Administrator School

Services (e.g. Librarian) Other ________________________________________________________

Any questions regarding this application, please email Dr. Karsonya (Kaye) Wise Whitehead at kewhitehead@loyola.edu.

EQUAL OPPORTUNITY STATEMENT: NVLP does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, national origin, age, genetic information, disability, or veteran status.

Dear Colleagues:

We hope you are as excited as we are about the upcoming 2017 Black Quilted Narratives (BQN) Summer Teachers’ Institute. We are thrilled to announce that the Institute will be held in Baltimore City’s Reginald F. Lewis Museum for Maryland African American History & Culture from July 10-21, 2017. Download the Application Here!

Application D/L: June 19, 2017

About the Black Quilted Narratives Program

Created by NVLP, BQN is a curriculum support package for elementary, middle and high school teachers that uses videotaped oral history interviews with visionaries from the Civil Rights Movement to guide students in discussions about social injustice, racial healing, and political activism. During the Summer Teacher’s Institute, teachers will learn the tenets of Culturally Proficient Instruction (CPI), while exploring one of America’s greatest evolving stories ever told—the Civil Rights Movement. The goals of the institute are: To create a space for 5th-12th grade teachers to deeply engage with the NVLP interviews; to learn and integrate new scholarly perspectives on teaching and learning; to examine the effectiveness of using primary source video material in the classroom; and to learn best practices for becoming a culturally proficient teacher. The institute is the second phase of a multi-year innovative teacher- training program funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF).

About the BQN Institute

During the two-week Institute, teachers will have an opportunity to:

- Train as a culturally responsive teacher—which includes watching and discussing visionary webisodes; examining primary and secondary source material with historians; and, participating in daily small break-out pedagogical sessions with support provided by BQN Master Teachers;

- Participate in racial equity training—which includes reflection activities, working and planning in small groups, and working with a Racial Equity trainer; and,

- Develop materials to plan and present a Professional Development Workshop.

Topics covered during the institute include the history of the Civil Rights Movement; women of the Civil Rights Movement, Racial Healing and Social Justice, and, Culturally/Politically Responsive Pedagogy (with an overview, hands-on demonstration, and tips for implementing this into your classroom).

Teacher Benefits

Classroom Resources: lesson plans, a primary source package, and access to BQN webisodes.

Stipends: selected teachers will receive a taxable stipend of $1,200. Participants are required to attend all course meetings and engage fully in the work of the project. During the two-week institute, participants may not undertake teaching assignments or any other professional activities unrelated to their participation in the project. Teachers who complete the institute will receive their stipend.

Continuing Education Credit: Teachers who complete the program will receive a certificate of completion and have an opportunity to apply for continuing education credits, which they may present to their home school districts.

Our Team

Cheryl S. Clarke (Co-Project Director), a former foundation director and teacher, is the Chief Executive Officer for the National Visionary Leadership Project (NVLP) since 2008. She directed the Foundation Giving program, created the Diversity program, and worked in Human Resources at Freddie Mac for 25 years. Prior to joining Freddie Mac, Clarke taught special education for seven years in the D.C. Public School system working with emotionally and behaviorally challenged boys.

Karsonya (Kaye) Wise Whitehead, Ph.D., (Co-Project Director) is the Curriculum Lead and Associate Professor of Communication and African American Studies at Loyola University Maryland. Dr. Whitehead is an award-winning former middle school Social Studies teacher (2006-07 Maryland History Teacher of the Year), a curriculum writer, and a Master Teacher.

Lawrence Brown, Ph.D., (Historian), is assistant professor in the Morgan State School of Community Health and Policy. His scholarly work focuses on the intersection of masculinity, racism, and health, the impact of residential displacement and financial disinvestment on community health, and understanding ethics and economic development in the domain of global health.

Brittany Horne (Master Teacher) is an elementary school teacher at Roland Park Elementary Middle School who previously piloted the BQN Teacher Institute.

Tracy Kent-Gload (Master Teacher) is an elementary school teacher at Ridgeway Elementary School who previously piloted the BQN Teacher Institute.

Nadiera Young (Master Teacher) is a middle school Language Arts teacher at Roland Park Elementary Middle School who previously piloted the BQN Teacher Institute

The documents are also available for download at http://loyola.academia.edu/KayeWiseWhitehead. All applicants must complete the BQN application form and provide the information requested to be considered eligible. Please send application packages to the National Visionary Leadership Project (NVLP) via email at kewhitehead@loyola.edu. If you have any questions about the Institute or application process, please do not hesitate to contact the Curriculum Lead, Dr. Whitehead, at kewhitehead@loyola.edu.

We encourage you to apply for this innovative Summer Teachers’ Institute focusing on the Civil Rights Movement and the men and women whose leadership during this time forever changed our nation. As you share the stories of these civil rights leaders with your students, and they share their stories of lessons learned from the material, you will help your students see the world in brand new ways and, perhaps, see themselves as being part of the greater American story—the great American quilt.

Sincerely,

Cheryl S. Clarke, Project Co-Director and CEO, National Visionary Leadership Project (NVLP)

and

Karsonya Wise Whitehead, Ph.D., Project Co-Director and Associate Professor of Communication and African American Studies, Loyola University Maryland

Originally published in The Baltimore Sun March 9, 2017

There is a movement for change that is happening in this country, and women are at the forefront of it. It is an incredible time to be a woman and, by extension, to be a girl. It is also exhausting, and it is hard work. It is a time of high hopes and great expectations.

We are standing tall giving ourselves permission to jump at the sun and say out loud that we are brilliant, resilient and we are here, fully present and accountable to this moment in history. We are protesting, organizing and making our voices heard throughout this world. The last two social movements in this country were founded and organized by women: Black Lives Matter was founded by three black women, and both the 2017 Women’s March (the largest United States protest in history) and Wednesday’s “A Day Without a Woman” protest were organized by women. We are using our pens, our voices, our art and our wallets to confront and dismantle racism and sexism and poverty and despair and violence.

Though the momentum for change is new, the work we are doing is not. Women have been our own champions for decades, since before Abigail Adams, the wife and adviser to President John Adams, urged the Founding Fathers to remember the ladies (obviously they ignored her). Women’s history and women making history is American history and a vital part of the American story. The contributions and sacrifices of women are part of the mortar that holds and binds our nation together.

We are now in the midst of celebrating Women’s History Month, a time when we highlight and celebrate the contributions of all women to events in history and contemporary society. We remember the women who worked to end American slavery; who challenged William Blackstone’s 1765 document, “The Rights of Persons”; and who pressured Congress to pass and ratify the 19th Amendment finally granting women the right to vote in 1920. We remember the contributions of women who acted individually and collectively to advocate for equal pay, for equal say and for our safety. Women who showed us every day that we have to fight, sometimes in the face of anger and humiliation, to be heard. Women who remind us, as Angela Davis once said, that we have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world.

The first Women’s History Week was celebrated in 1978 in Sonoma, Calif., and begin to spread across the country. Two years later, President Jimmy Carter issued a presidential proclamation declaring the week of March 8 as National Women’s History Week. The proclamation states in part that, “From the first settlers who came to our shores, from the first American Indian families who befriended them, men and women have worked together to build this nation. Too often the women were unsung and sometimes their contributions went unnoticed. But the achievements, leadership, courage, strength and love of the women who built America was as vital as that of the men whose names we know so well.” By 1987, Congress issued a resolution designating March as Women’s History Month. Today, it is celebrated all over the world and corresponds with International Women’s Day (March 8).

At the same time, there is still so much work to be done. Even though women are 51 percent of the population and currently make up 57 percent of the students in colleges or universities, we are still fighting for basic rights:

• Women are paid only 80 cents for every dollar paid to men for full-time year round work, and for women of color, the wage gap is even larger;

• Only 20 percent of Congress, 27 percent of U.S. college presidents, and 33 percent of U.S. state and federal judges are female;

• And each year, more than 300,000 women are raped, 2 million are battered, and more than 1,000 women are killed by their husbands or boyfriends.

This must change, and this is how we do it: We recognize that men still run the world and work to change and confront that truth; we focus on closing the gender gap and breaking all glass ceilings; and we raise our daughters and our sons as feminists, help them to find their voices, and send them forward to change the world.

Karsonya Wise Whitehead (kewhitehead@loyola.edu; Twitter: @kayewhitehead) is an associate professor of communication and African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland and the creator of #ADayWithoutAWoman K16 Syllabus. A version of this editorial was aired as a public commentary on WYPR 88.1, Baltimore’s NPR station.